The Rise of the Spectrum: Afua Hirsch dissects the rising rates of ADHD and autism in women and girls

An “awareness boom” is raising rates of ADHD and autism, particularly among women. Now, they’re discovering the truth behind years of quiet struggle — and rewriting what neurodivergence looks like. Afua Hirsch investigates.

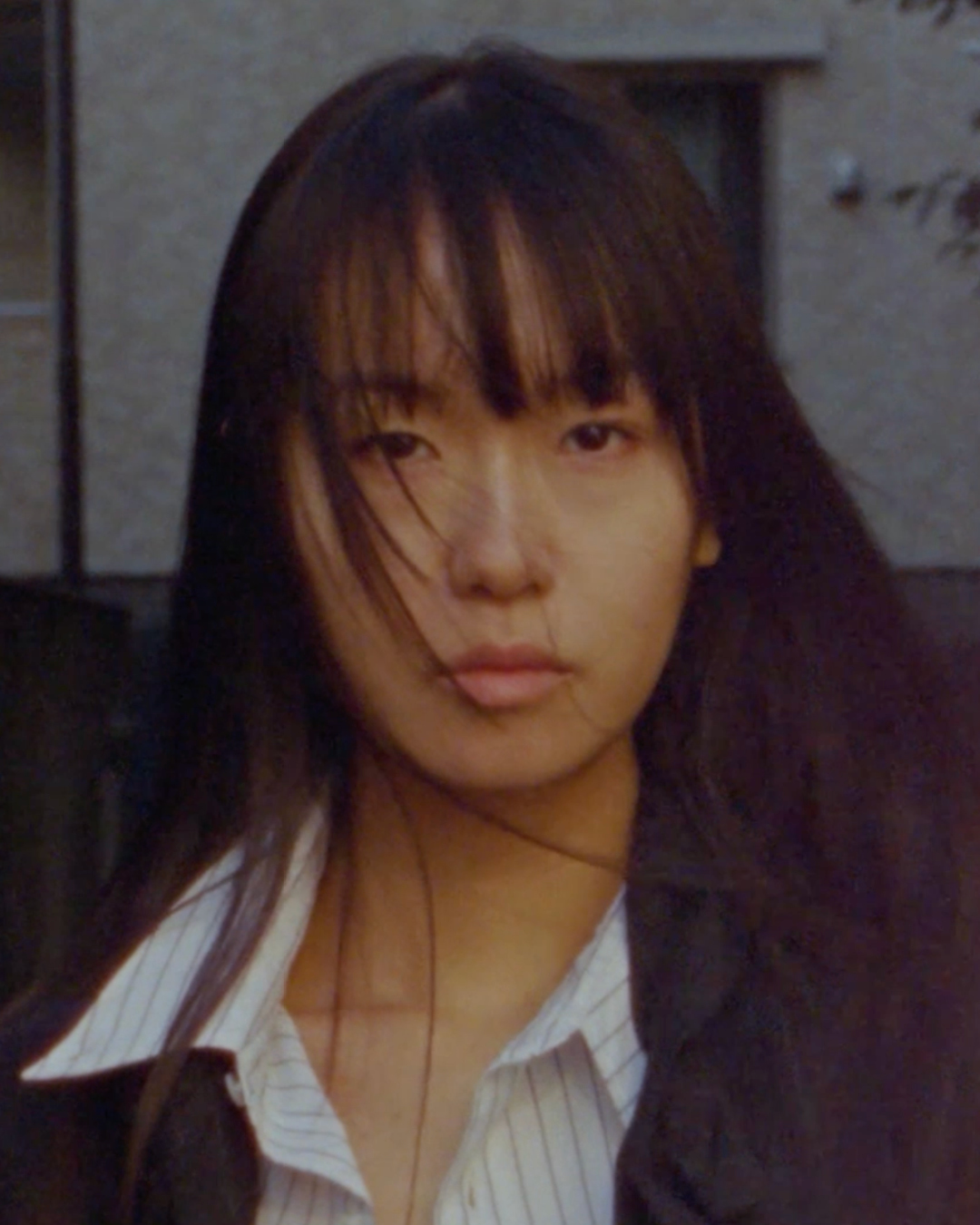

In person, Helen Lawal is exactly as she appears on TV. The exuberant doctor, nutritionist and coach is also gorgeous, with a head of beautifully full afro-textured curls, and an undeniable Yorkshire lilt. Over recent years, Lawal has become an in-demand presenter on UK shows like Food Unwrapped and How to Lose Weight Well.

But in 2020, as she dealt with the multiple challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, giving birth to her TK child, and experiencing postnatal depression, something unexpected happened. “I tried to go back into work as a frontline worker, and I couldn’t. I had what you would call I guess a breakdown,” Lawal says. “I saw a psychiatrist, and that’s how my ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) diagnosis came about.”

As Lawal was grappling with this revelation, another swiftly followed, revealing she was also autistic — a spectrum characterized by differences in social interaction and communication, and by restricted or repetitive patterns of thought and behavior. “It’s taken me four years to talk about my autism personally,” Lawal reflects. “I was brought up by a white Mum in a white market town in [England’s] rural north Yorkshire — I had never seen or met anyone who looked like me or came from my background who was autistic or had ADHD.”

Lawal is one of an exponentially growing number of girls and women newly discovering their neurodivergence. In the UK, ADHD was once seen as a childhood phenomenon, but adults now make up almost 60% of all treated cases, one third of those, women. It’s being described as an “awareness boom” revealing — as charity ADHD UK puts it — “the historical and ongoing failure to recognize ADHD in women and girls”. For autism, the picture is even more stark. In the two decades between 1998 and 2018, autism diagnoses increased by 787%. In the past, the emphasis was on boys and men, whereas now the largest increases are driven by girls and women. Researchers say autism manifests differently across genders. In the playground for example, autistic boys tended to play alone. Psychologists looking for signs of social isolation therefore overlooked many autistic girls, who had high levels of what scientists’ call “social motivation”, craving friendship, and experiencing a strong need to belong.

Autistic women often develop ways of “masking” — learned strategies to conceal their social difficulties. While this has led to some autistic women considered “high functioning”, there’s a growing sense this obscures the true cost of not being oneself. One survey found that adults who had been masking their autistic traits were exhausted, lonely, questioning their friendships, and confused as to which parts of themselves were real, and which a performance meant to disguise their neurodivergence.

“Terms like ‘high functioning’, and ‘low functioning’, are really dangerous,” says Lawal. “What it means is that we have got very good at masking. And we know that masking is a risk factor for suicide, because it’s so draining, to spend half of your life pretending to be someone else.” In her own life, Lawal found that performing on TV, then performing in real life to mask her autism, was doubly draining. “On the surface, it looks like I had a really enjoyable career, I travelled the world, meeting people. But behind the scenes I was struggling. I was in pain. I had migraines. I experienced all of these things because of the stimulation and the sensory overwhelm. And so, you get really good at masking.“

Lovette Jallow is a mesmerizing person to interview. Born in The Gambia before moving to Stockholm, where she is now based, only the slightest inflection of Swedish accent is audible in her voice. She wears a bright red head wrap styled over long hair, flawless makeup accentuating her almond shaped eyes. “Autistic people, we like to have our ears covered,” she laughs.

Jallow, who is an author, lecturer, activist, and describes herself as a “strategist working at the intersection of neurodivergence, race, and structural design”, came to my attention on Instagram. Her intricate, colorful posts offer insights into African and other indigenous knowledge systems’ approaches to neurodiversity. Terminology which, she states at the outset of our conversation, is important to get right. There is “neurodiversity”, which Jallow describes as encompassing everyone, “like biodiversity for minds,” she explains. “Every community contains multiple neurotypes”. A “neurodivergent person” is one whose brain functions diverge from the statistical norm, whereas a “neurotypical person” has cognitive processing that aligns with the statistical norm for a given culture.” Jallow is conducting research into African cultures which questions the idea that this norm remains modeled on western ideas.

When I lived in The Gambia, I did not know I was autistic. I knew my grandmother loved me and structured the world so I could thrive. After moving to Sweden, where both my Blackness and my neurotype were marked as strange, I understood what had been protective about that early belonging. That rupture became my research.

Doctor, nutritionist and coach, Helen Lawal

“When I lived in The Gambia, I did not know I was autistic,” Jallow shares. “I knew my grandmother loved me and structured the world so I could thrive. After moving to Sweden, where both my Blackness and my neurotype were marked as strange, I understood what had been protective about that early belonging. That rupture became my research,” she adds.

Jallow explains how the destruction of precolonial traditions, and the negative experiences of Black people with services have combined to make neurodivergence stigmatized among Black communities. In the UK for example, Black men are three times more likely to suffer degrading ill treatment and detention on grounds of mental health. “Many Black and brown families recognize [neurodivergent] traits but refuse the terms, because those terms came from systems that pathologized us, erased our knowledge, and replaced Indigenous ways of being,” Jallow says. “And they are scared, because what happens to us [in this system]? We get institutionalized, and we get killed”.

It strikes me that all the women I spoke to for this feature all embarked on careers studying neurodivergence, achieving professional success for several years, before they discovered they were personally neurodivergent too. “Catherine”, a psychologist I spoke to who asked that her name be changed, has just such a story. As a professional with years’ experience assessing autism in others, she is still processing the recent diagnosis that she too is autistic. “If I wasn’t working in schools and seeing as many neurodivergent children as I am, there’s no way I would have considered it for myself,” she said. “And even with that it took me this long to realize!” Despite her deep knowledge of autism in others, discovering it in herself is a shock. “I’m taking my time to process it. I have got some internalized ableism that I’m trying to unpick.”

That stigma is not helped by language which frames neurodivergence as a problem. “The language that’s used in these processes — “disorder”, “deficit”, “struggles”. It’s all based on negativity and the things you found difficult,” says Lawal. Catherine felt that the growing number of celebrities opening up about their neurodivergence, including Professor Green and Cat Burns, had helped her tackle those views. “I know a lot about neurodivergence, how it shows up, how to support it, how to make adaptation, and yet even I find it so surprising that Cat Burns is autistic,” said Catherine. “I still have an internalized view of Rain Man in my head.”

The Rain Man paradigm — a reference to the 1988 Oscar-winning film which brought awareness of male autism into the mainstream — is often referenced as a reason neurodivergent women have been ignored. That depiction, in which Dustin Hoffman’s character is an autistic man with remarkable savant abilities, bears no resemblance to what girls and women are most likely to experience, says Tiffany Nelson, a London-based child, community and educational psychologist. And especially not Black girls. “My daughter got diagnosed with autism when she was two,” says Nelson. “At that time, in 2013, they were still only really diagnosing boys. My daughter was in a specialist nursery. She was often the only girl.”

“Then, when I started doing my doctorate, I had a few questions about myself. I saw a psychotherapist, and was talking about my daughter, when she said, ‘this is a real mirror of you!’” Nelson recalls. “I realized that was why I was doing the degree — I was trying to make sense of myself!” Nelson is convinced it’s no coincidence that diagnosis happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. “A lot of people became quite anxious — we allowed ourselves to be late to things, to not get dressed-up, to be more relaxed, and to assert some of our needs. I noticed that shift.”

One expert describes the pandemic as having had dramatic effects on awareness of neurodivergence. By its end, ADHD became the second most-searched condition on UK health authority the NHS’s website, and autism diagnoses peaked. “Many adults sought diagnosis for the first time, prompted by disrupted routines, introspection, and online dialogue about neurodivergence,” writes Dr Asad Raffi, a psychiatrist and ADHD specialist. “For some, pandemic stress unmasked traits that had long gone unnoticed.”

Yet it does not take a global pandemic for women to tire of the masking many have learned to make their neurodivergent minds “fit” the mainstream. For Black women in particular, the growing discourse around trauma and burnout also have their role to play. “We are traumatized, and if we are being honest about it, we don’t want to be “strong Black women,” says Jallow. “If we have to be strong for others to be soft, we don’t want it.”

“So, people are saying ‘I am disabled’. I can be strong for you, but it’s not one way, it needs to be reciprocal. We can’t code switch and mask. How much more can we bear?”

The sense of exhaustion is often exacerbated by hormonal changes. Although there is still little research on how this affects women, doctors and psychologists are convinced of its impact. “What I hear from women is how much harder it is during puberty, postnatally, perimenopause, menopause,” says Lawal. “It’s a tipping point for a lot of women, where we are seeing a lot of diagnoses. Perimenopause is stripping them of their last means of coping.”

There is still too little awareness, Lawal insists, on the intersection between neurodivergence and other issues that affect women’s health, particularly nutrition and diet. The correlation between ADHD and disordered eating has become Lawal’s “niche within the niche”, she explains, again driven by her own struggles. “All through my training as a junior doctor, I experienced binge eating, sugar cravings, this inability to get into a routine, with going to the shops, cooking, meal planning, shopping, and exercising. It feels really shameful when you’re a medical professional and this is what you’re telling other people to do,” Lawal says. “When I thought about my own life, and why I had found these things so difficult, it’s because I was trying to do it the neurotypical way.”

It’s taken me four years to talk about my autism personally. I was brought up by a white Mum in a white market town in [England’s] rural north Yorkshire — I had never seen or met anyone who looked like me or came from my background who was autistic or had ADHD.

Author, lecturer, activist Lovette Jallow

Lawal now coaches ADHD women on how to manage nutrition in a way that works with their neurodivergent brains, rather than against them. “Think about ADHD typical symptoms of restlessness, hyperactivity, emotional dysregulation, executive dysfunction,” Lawal suggests. “You need a good level of executive function to meal plan, to do a food shop, to go to the supermarket, because it involves planning, prioritizing, following through steps in a timely order. This is something ADHD people are struggling with on a daily basis,” she adds.

Like many areas of neurodivergence in older people and young adults, there is still shockingly little research. The same is true for the relationship between neurodivergence and sexuality, Jallow says, leading her to conduct her own surveys. “In my community a clear pattern repeats. After an autism diagnosis, many people recognize they belong to other spectrums; queer, ace [asexual], trans,” says Jallow. “Emerging research shows autistic people are several times more likely to identify as LGBTQ+. Some suggest autistic people are less constrained by social scripts around gender and sexuality… both autism and queerness require a lifetime of translation in environments not designed for us.”

The growing confidence of neurodivergent advocates has its detractors, with Donald Trump recently decrying the rise in cases as a “horrible, horrible crisis.” The comments prompted an immediate backlash, questioning his evidence, as well as the suggestion that neurodivergence is a problem to be cured. The neurodivergent women I spoke to agreed that while presenting its challenges, the fact people were better aware of how their brains work was unequivocally a positive thing. “Rising diagnoses are not a moral crisis,” Jallow says. “They are a correction, because people finally feel safe enough to describe their minds in language that fits their culture.”