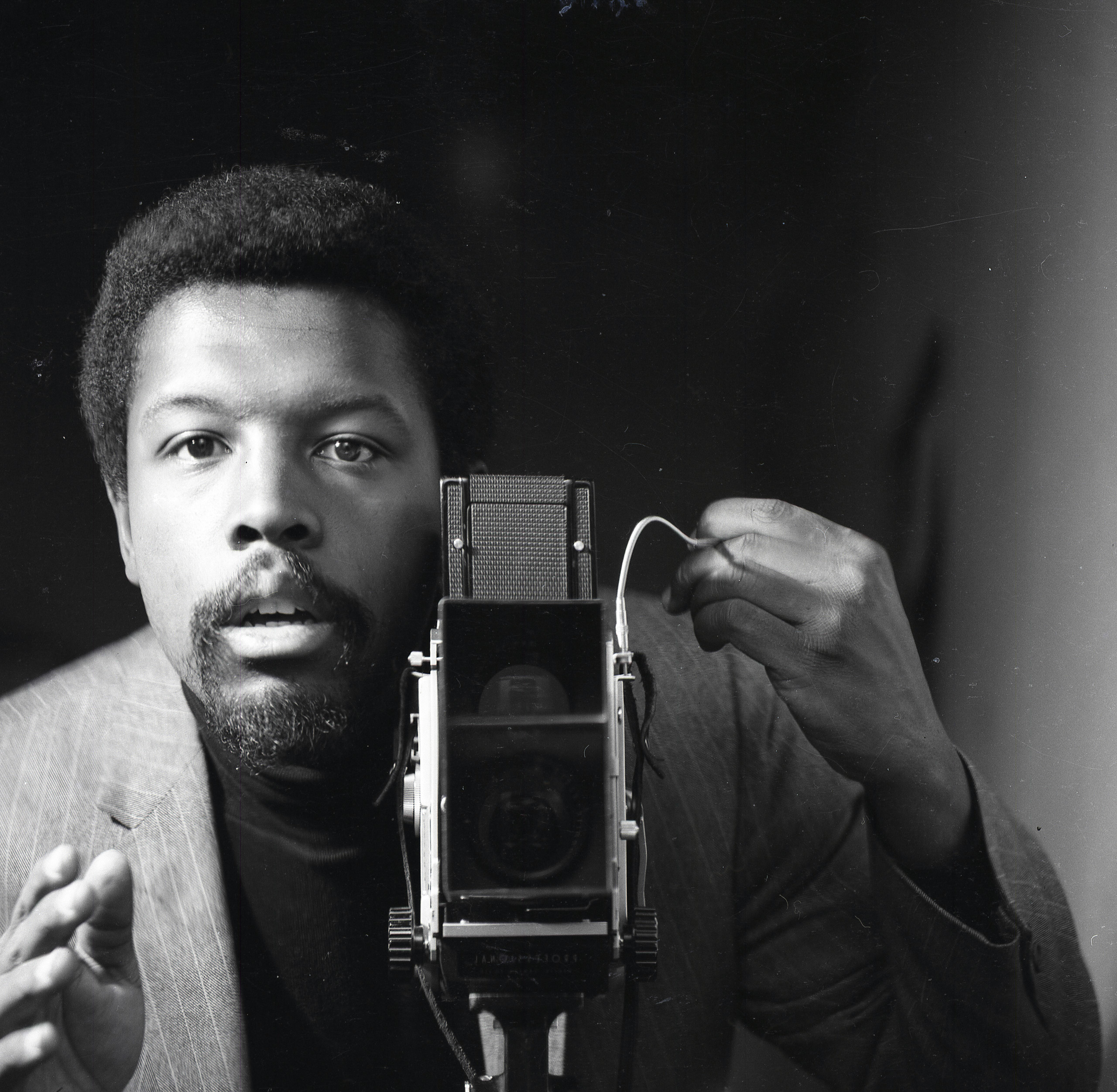

From Harlem to Dakar, Kwame Brathwaite’s images sparked a global movement. Yemi Bamiro’s new documentary, which premiered at the BFI London Film Festival, brings his revolutionary vision back into focus.

Ask most people about the civil rights movement, and Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X are the names that immediately surface — symbols of political and economic transformation. Less known internationally is the role of American photographer and activist Kwame Brathwaite in the cultural revolution of Black people in America and beyond.

From the early to late 1960s, he championed the Black Is Beautiful campaign, a movement celebrating African American identity and aesthetics. Central to this effort were the Grandassa Models — women who embraced natural hair and African-inspired style outside Western beauty norms, staging fashion shows and events to make these ideas visible to the wider world. This movement used photography as a tool for representation and change.

Yemi Bamiro’s new documentary, Black is Beautiful: The Kwame Brathwaite Story, which is in competition at the BFI London Film Festival, highlights this lesser-known part of cultural history. “We’re familiar with lost histories, but I have been a patron of the arts for a long time and had never been in a situation where such an established guy with half a century’s impact on us, the general public, couldn’t name,” says actor Jesse Williams. He’s one of the celebrities interviewed alongside Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz, Gabrielle Union, Tyler Mitchell and members of Brathwaite’s family and friends.

Born in Brooklyn in 1938 to Barbadian parents, Brathwaite grew up in the Bronx and spent time in Harlem, a hub of Black creativity. His wife Sikolo believes that seeing a photo of Emmett Till’s brutalised, bloated body at his funeral left a profound impression on the teenage Brathwaite.

Brathwaite’s career spanned over 60 years, capturing icons such as Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali, Grace Jones, and Bob Marley, as well as everyday people whose beauty and power he saw reflected in his lens. A pan-Africanist and activist, he and his brother Elombe Brath founded the Africa Jazz Arts Society and Studio (AJASS) in 1956 to empower Black people aesthetically, politically, and economically — a mission that shaped much of his life’s work.

KWAME BRATHWAITE. Courtesy of the KWAME BRATHWAITE ARCHIVE

As an activist, Brathwaite hosted dinners and meetings, but due to his involvement with anti-colonial movements in Africa and political work for the liberation of Black people in America, he faced FBI surveillance. However, he continued his activism. His work embodies the hope that Black stories include both joy and resistance, reminding the world that Black is beautiful.

Brathwaite’s son, Kwame Samori Brathwaite, and members of his family have spent the last few years working to preserve his legacy, bringing his photographs to the world’s attention. “He changed the way people see themselves”, says Kwame Jr.

Adds Tyler Mitchell in the documentary: “His work has inspired me hugely. The beauty and role of photography is not to just exist in a vacuum but to reflect the times.”

We sat down with Bamiro to learn about the making of the documentary and Brathwaite’s lasting impact on style, identity, and social consciousness. Known for his work spotlighting underrepresented stories across art and history, Bamiro brings his signature depth and visual storytelling to Brathwaite’s life — this time with Brathwaite’s family to tell his story from the inside out, with honesty, authenticity, and insight.

EE72

How did you become involved with this project and develop the film?

Yemi Bamiro

What’s really funny about this story is that a friend of mine had bought me the book [“Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful” by Tanisha C. Ford and Deborah Willis] two years before I started talking to the production company about making it. And then in July 2023, not long after Kwame passed away in April, I got a message from Lizzie Gillett, who’s one of the producers on the film, and she said do you want to have a conversation about making this film? That conversation basically advanced with me having a Zoom call with Kwame Jr. We spoke about what the film could be and then we started paid development where you’re just developing the idea. Part of that was me going to California to meet Kwame Jr. and see the archive. We’ve been working on this film for about two years, but it all started with one of the producers getting in touch and thankfully, I already had a knowledge of him and I had the book, so it just felt like the stars aligned.

EE72

As you saw his archive in California, did it prove to be a challenge sifting through his extensive archive shot on film and condensing it in a way that could be presented for the screen?

YB

Yes, it was challenging, but the remarkable thing is that it’s a living, breathing archive. His family has only been through a small percentage of the 500,000 photos he took during his lifetime and every single day, they are discovering new photographs. Was it overwhelming? Yes and no, but we had the guidance of the family, who are archivists. They do this work every day, selecting the best pictures to exhibit in galleries globally. We followed their lead, asking if they had anything like this or that. They would then come back with a list of images. It was a collaborative process with the family working specifically on the archive, and it felt like a privilege to be able to examine it, especially since much of the archive had never been seen before.

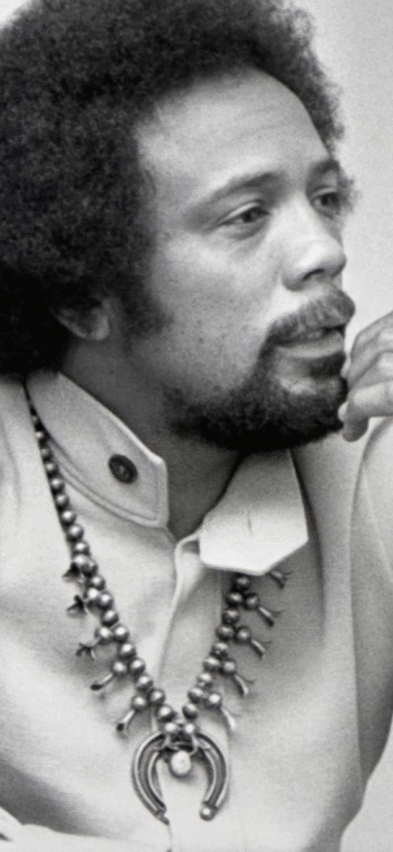

Courtesy of the KWAME BRATHWAITE ARCHIVE

Courtesy of YEMI BAMIRO

EE72

“Black is Beautiful” is divided into chronological chapters based on different time periods, like 1974 when Kwame traveled to the African continent. During this time, he photographed the Jackson 5 who performed in Dakar, and he later visited other countries including Nigeria, Sudan and Tanzania. It’s clear that a lot of time was spent on the research, showing a level of great care in telling the story. What was your research process like, including reference points such as anecdotes from family members?

YB

One of the challenging aspects of this film is that there was so much story. We could have made another film because Kwame’s life was extensive and he wore so many hats. Otto Burnham, the editor, who also co-wrote this film, would always say, there’s just so much story but in order for it to work in the film, it’s got to have meaning. It’s got to connect to something. You can’t just throw a story in for the sake of it, it has to make sense. That was one of the challenges and it was also like, how can we tell the most compelling story about his life? We had help from his family and we had a roadmap based on his life on what he did. For example, we know that during these years, he was at the Apollo Theatre in New York or on the African continent. We know that between certain years, he was primarily in Harlem, working on AJASS projects. We had a long edit and we had the space and time to work out what it is. That’s also a testament to Otto and Lwimbo Kunda, who is the associate editor.

EE72

I can imagine you had to be a bit brutal with the editing.

YB

Absolutely, you should have seen our edit room. It was filled with post-it notes everywhere. We would have these sessions where we’d sit down and try to plot the film. They were intense but Otto and Lwimbo were great with editing. It was all a very creative collaboration. Everyone involved in the making of this documentary film pulled in to ensure that we made the best story.

EE72

While researching more into Kwame Brathwaite’s life and watching “Black is Beautiful,” I was surprised to find out how underrated he is, given his decades-long career photographing iconic figures such as Bob Marley, Nelson Mandela, and Muhammad Ali. Would you say this documentary provides a good introduction to his life and could serve as a starting point for other film or TV projects focusing on different areas such as his activist work?

YB

You’re right. It’s a great jumping off point for people because it feels like we are living in an age where the contributions of Black and brown people are being erased, underappreciated or diminished. This film is significant because it is a testament to his work and legacy but Kwame is not the only one. There are other people out there who made huge contributions that haven’t been given their flowers in the right way so if this film can lead to other films that highlight heroes and icons in society, that’s a great thing.

EE72

How do you balance the responsibility of storytelling as a filmmaker with the reality of being involved with the subject’s loved ones?

YB

We had a really good relationship with the family. I will always have deep respect for them because it’s not easy to share details about someone’s life. In this case, to tell people you haven’t known for very long, this is the archive. This is who my father was. It’s not easy and I would struggle with my mum to do that. I don’t know if I could do something like that so it was a brave thing from Kwame’s family. We collaborated closely with them. They reviewed edits, provided notes, thoughts, and feelings, but always with the spirit of making the best film about this man and Elombe (Kwame Brathwaite’s brother) and the legacy they built. Everything was to serve the film.

EE72

This is important, as there have been instances with projects of a biographical nature where the collaborative balance isn’t present.

YB

Yes. It didn’t happen with this film. We all pulled in the same direction. We didn’t always agree on everything which is expected, but it’s all part of the creative process. We made sure to listen to each other and ultimately, we made the film based on our collective input into what is on screen.

EE72

When starting a new project, what tends to go through your mind? Do you have an idea of what the finished work is going to be, or do you leave the work open to continually evolve and take a life of its own?

YB

With this project, because we had development, which, part of it was to write a comprehensive treatment — a sort of script for the film, I remember doing a moodboard for “Black is Beautiful” and that was significant because we would give the moodboard to the graphics people, the colorist, the crew and the production designers. It didn’t use lots of words but it was more so pictures, images and iconography as references that people responded to in a way that they didn’t necessarily respond to the treatment because the treatment was very long and dense. The moodboard is what opened people up and got everyone excited about the film and visualised what it’s going to be. Once we had locked that down, it was all about the research and reaching out to people.

EE72

Some of the projects you’ve directed include “Fight the Power: How Hip Hop Changed the World,” the recent “Trainwreck: The Astroworld Tragedy” documentary and “Hate Thy Neighbor” for Viceland. The latter highlights the pressing problem with the far-right movement that’s been escalating. Could your work be considered a form of social history, presenting both the past and the present? And how do you find these stories to tell?

YB

What I think about “Hate Thy Neighbor” is that it was a cautionary tale about where we are today. We made it during the first six months of Donald Trump’s first term as president. Everything that has happened over the past eight years, we called it in that series. I think about that all the time. And when it comes to whether my work is social history, I definitely respond to that. I’m interested in society and the way we are as people, our legacies, and the cause-and-effect thing. But ultimately, at the heart of all of that are people — interesting people. Though they might hold views you don’t necessarily agree with.

EE72

Like in “Hate Thy Neighbor.”

YB

Exactly, most of those people had views I disagreed with, but they were fascinating characters. They didn’t exist on an island. There are people who share those views and that’s interesting because where did that come from? So I would say that my work is a study of people. That’s what sociology is and I’ve always gravitated towards that.

EE72

What inspires you in your filmmaking practice?

YB

Whenever I think about “Black is Beautiful: The Kwame Brathwaite Story,” I feel privileged and grateful to have had this opportunity to make this film. It never felt like work. It always felt like this is crazy, we’re getting a chance to make the film and bring the story to life. And that’s the goal, that’s what inspires me. To find projects that give you that same feeling that it never feels like it’s work, a chore.

EE72

This is your third film in five years to be screened at the BFI London Film Festival. This time, the project is in competition, which is incredible. What does this moment mean for you and everyone involved with the documentary?

YB

It’s mad. It’s still crazy to me that this film is in competition. And like you said, this is the third film I’ve had at the festival and it’s always an amazing feeling. I’m a Londoner. I was born and bred in this city and I’ve been going to the London Film Festival since 2007. I’d go every year and be like okay, I’ve got £100 and I’m going to spend it on as many tickets. I’ve been a huge fan and to have the opportunity to show work at this festival is always very special. Also, many members of the crew are from London. The film is edited and produced here so it all feels like a homecoming for us.

This interview has been edited and condensed.