Albert Watson on the art of great image-making.

Photography Albert Watson

In his new book, Kaos, the legendary photographer looks back on five-decades of era-defining celebrity portraiture and beyond.

Photographer Albert Watson’s new book Kaos is as much a journey through 50 years of Western culture as it is a monograph of his work. It’s a cinematic, elevated retelling of events. Pick a legend in music, film, art, literature or fashion from the late 1970s onwards, and you might find not only their portrait in this book, but their best-known one, too. Album artwork, film posters, magazine covers – Watson lends his subjects the same grandeur as forebears like Avedon, Brassaï, and Penn, but continually plays with the form and the alchemy of an image. There’s surrealism, subversion, drama, and other times a more quotidian truth, like a simple black-and-white Polaroid or a barren Scottish landscape.

Skye, 2023

The bottom line is, I was never a landscape photographer, or a still-life photographer, or a celebrity photographer, or a fashion photographer. I was all of these things, but what I hope you get from the book is, this guy is a photographer.

ALBERT WATSON

More than anything, Kaos is a reminder of the power of a meticulously crafted big fashion image, the kind of supermodel-starring, on-location mega-shoots that have slowly disappeared now that intimacy and realism have become such dominant ideals – part by design, mostly by necessity. In that sense, Watson’s book also captures one world giving way to another. “I used to have a meeting with a magazine, and they’d say, “Okay, where would you like to shoot this winter?” he recalls.

Over the phone from his studio in New York, Watson talks openly and enthusiastically about his work, nostalgia and the best (and worst) celebrities he ever shot.

Naomi Campbell, 1989

I saw the Cecil Beaton exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London recently, and what struck me was not so much how technology or styling has changed, but how much the world, culture and celebrities have changed. In some ways, the baton was passed from a photographer like Cecil to you, in that you pick up where he finishes. Do you relate to that feeling at all?

I was not a big fan of Cecil. That does not mean he was not an important person. He was. I thought he was a better designer, but he lived in a time when he had access to a lot of celebrity, access to fashion, being famous for the fashion world he lived in. I met him once and chatted with him, and I found him to be very nice and friendly. American photographers like Avedon and Penn were the ones I was more fascinated by, especially Penn. They were a bigger influence on where I was going. What was a little unusual for me is that I was involved in many different genres. When I did Cyclops (1994), I had a lot of problems with the publishers because they wanted me to do a book of celebrities. Instead, I approached it almost like Instagram. With Instagram, you never know what is on the next slide. It can be a kitten licking milk, a soccer game, or a girl running in a bikini. I thought a photo book was more interesting if you had a fashion shot, a celebrity, then a portrait of a man on death row at Louisiana penitentiary. That was in 1994, and nobody had done something like that before.

In my experience, photographers never want to label themselves as nostalgic. It is so often about looking forward. But with a project like this, where you go through your entire archive and look back into these little vignettes and worlds that are gone, do you feel nostalgic?

I do, but I am pretty locked into keeping up to date with what is on show now and what is available now. I am always searching for something that surprises me. A very well-known editor of a magazine looked at some pictures I had done for her 20 years before. She said when she ran the pictures she quite liked them, she was not crazy about them, but now they look really important. The same pictures. You are asking about nostalgia. I think it is possibly because stylistically, when I was doing fashion, I tended to do photographs of fashion as opposed to a fashion shot.

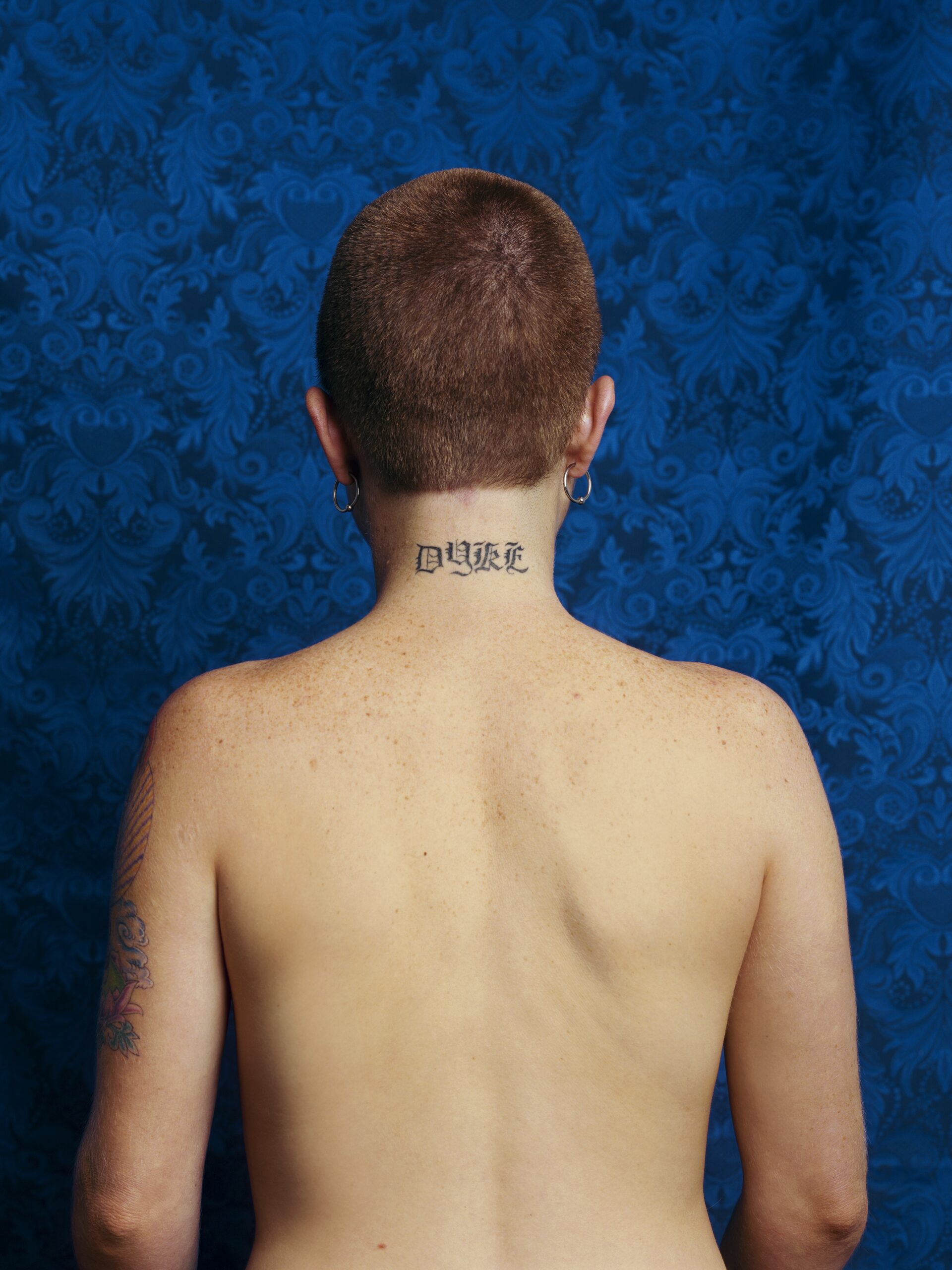

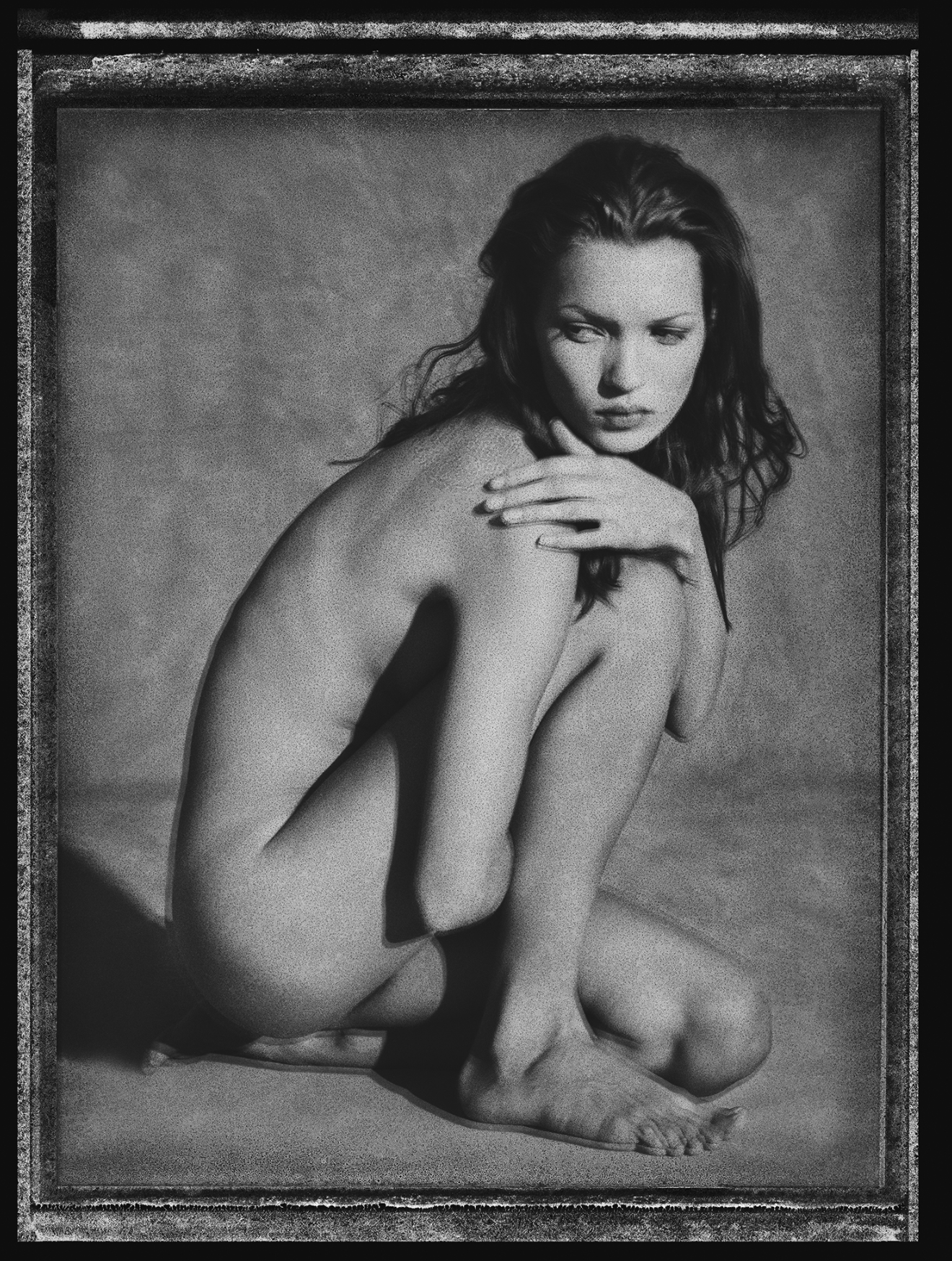

Kate Moss, 1993

What is the difference between photographs of fashion and a ‘fashion shot’ to you?

Sometimes I would do work for a magazine that was very handheld, very easy, spontaneous. A girl walking down the street eating ice cream, and you would give it to the magazine and they would love it. But when I came to do a book, I found that some of the most successful things that ran in a magazine weren’t heavy enough for a book. Sometimes a fashion picture takes a journey. It goes from a magazine and there’s a big jump into a coffee table book, then an even bigger jump onto a gallery wall and an even bigger jump onto a museum wall. There’s a subtle difference between a beauty shot and a portrait. The difference for me is the weight and the character of the person in front of you.

Looking through this book, I found that there were images that predate some of these photographers that we now know as having such a defined style. There are shots that feel absurd, like Tim Walker, or subversive, like Steven Klein, but these were taken 30-plus years ago. I can see a lot of what came next in photography in this work.

I think one of the best compliments I got was when Cyclops came out in 1994. I was in a restaurant and somebody tapped me on the shoulder and I turned around. It was Annie Leibovitz. She said, “I just went through your book.” I said, “Oh yes,” and she said, “I found it to be a very, very strong collection of work.” I thought, well, coming from her, that was a good compliment! I think it was the diversity of the work in the book that was fresh at that time.

Putting this book together and looking through your archive, has your relationship changed at all with the notion of celebrity, fame and excess? The mood around it certainly has.

The celebrity thing is different now, but in some ways the same. It’s more fleeting now, because sometimes there are people that in the past, from the 50s, 60s, and going back earlier, you mentioned Cecil Beaton, you had to back it up. Now you can be famous for cutting a wedding cake almost, and something goes wrong, the cake falls over, and everybody laughs, and you get 10,000 views on Instagram.

Jude Law, 1995

Celebrity is more fleeting now… In the past you had to back it up. Now you can be famous for cutting a wedding cake, and something goes wrong, the cake falls over, everybody laughs, and you get 10,000 views on Instagram.

ALBERT WATSON

This book is a tribute to a type of star that doesn’t really exist anymore. It feels like every great celebrity of the 20th century is included, and not only included, but is sometimes their best-known picture. Did it ever feel that way when you were shooting?

Take Clint Eastwood. He came into the studio, and he was a bit grumpy. But he’s six foot three, six foot four tall, massive, and he walks into the studio, and he looks amazing. I remember doing the first Polaroid of him, and he said, “Can I see the Polaroid, please?” and I showed him. This is a very nice moment. He said, “Okay,” and he handed it back to me, and he said, “Can you do me a favour? Please don’t sell that shot to anybody else. Give it to Rolling Stone, but don’t let anybody else use it, because I want to put it in my biography.” I think he saw right away that that was an iconographic image of him, that it was kind of a Mount Rushmore, chiselled version of who he saw himself as, something iconic. Years later, I went down to the White House to photograph Bill Clinton when he was president, and he brought me that picture of Clint Eastwood, and he said, “Can you make me look like this?”

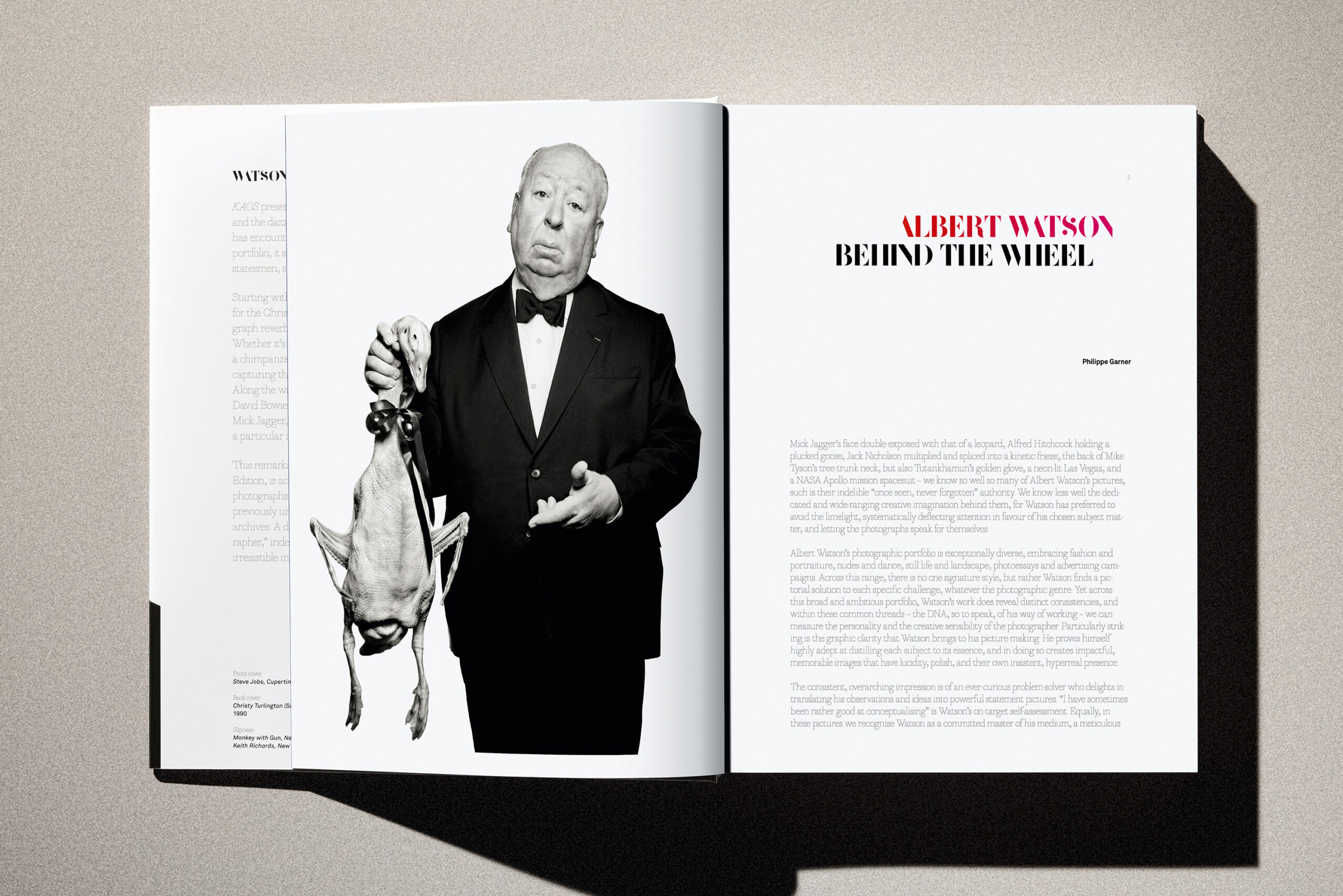

I read that Alfred Hitchcock was quite involved in that shot of him holding the Christmas goose too.

He didn’t make the suggestion of the goose. That was pre-planned. The reason for the goose was he was in the Christmas issue of Harper’s Bazaar. Apparently, he cooked the goose every year for Christmas and he gave his recipe. It was when magazines did things like that. So the shot that I did was illustrating that. He helped me and made suggestions, he became an actor with the goose and suggested different things. He started to cry at one point because he felt badly for the goose. I was lucky that he was like that.

Alfred Hitchcock, 1973

That image opens up the book. If your archive was on fire and you could only save one image, which would it be? The Hitchcock one?

Yeah, not because it’s the best photograph. I think there are other pictures in that book that are much better than the Hitchcock shot, much better. Better lit, better power, better intensity. However, that was a turning point for me, and therefore that’s why it was important, because it was a boost, it was a lift. Therefore, that is the one that I would put on a wall in my apartment.

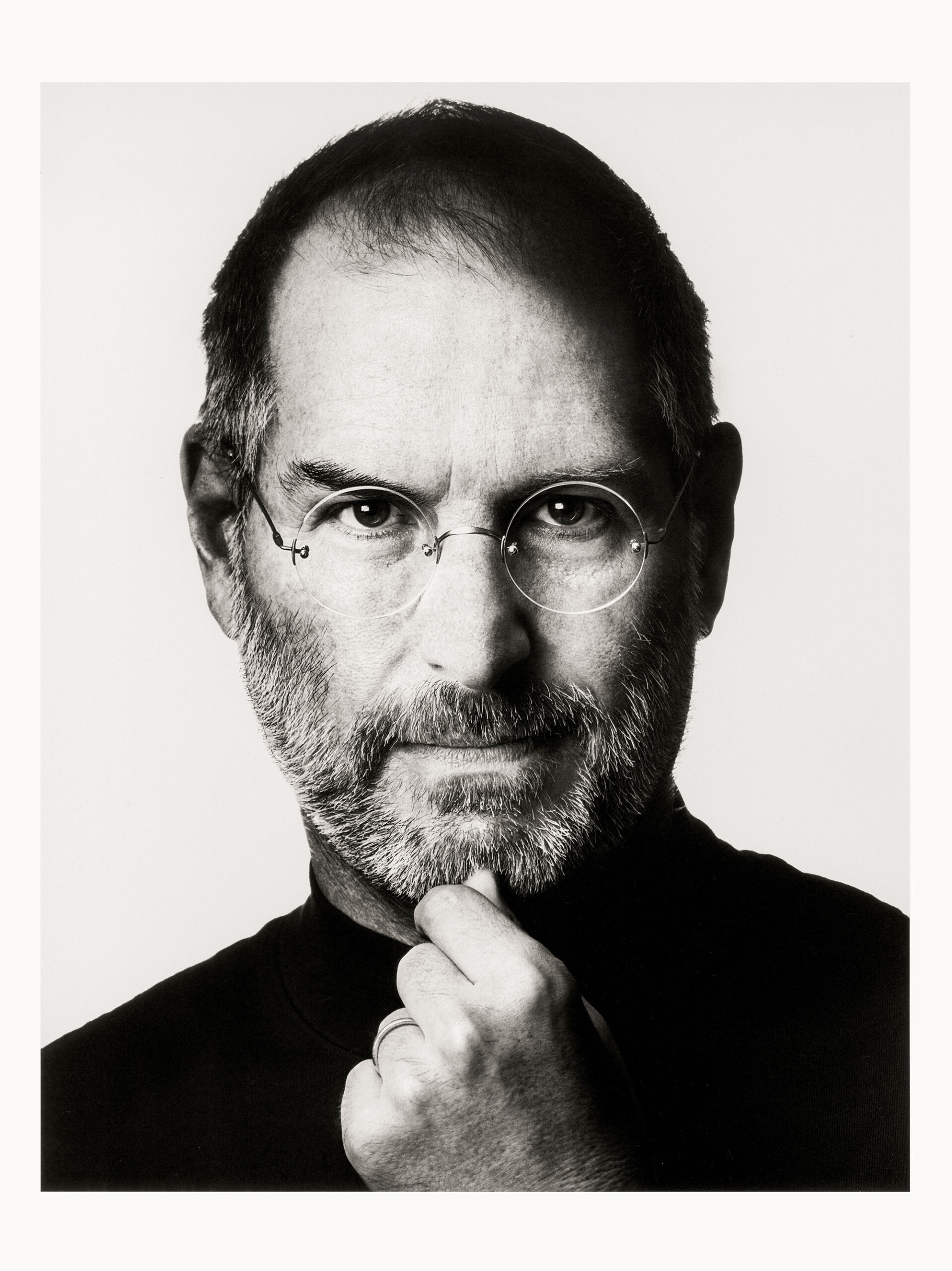

The Steve Jobs one features right at the beginning, too. I assume that picture has a big significance to you.

I think, strangely enough, there was a similar effect with that picture of Steve Jobs to the incident I mentioned with Eastwood. I took a four-by-five-inch Polaroid, and I put it in a small black frame. As he was leaving the shoot, he saw it, and he said, “I love this. Can I have it?” I said, “Sure.” He said, “Wow. That’s maybe the best picture ever taken of me.” Then, a few years later, I got a call from Tim Cook. He said, “Do you still have that shot of Jobs that you did? I need it immediately. I need it within half an hour.” I said, “I can send it in the morning.” He said, “I need it now,” and so on. I said, “Okay.” So we did it and sent it to him. When I was at the opera that night, my phone buzzed and he had died that afternoon. They used that shot on the Apple website worldwide.

Steve Jobs, 2006

Final question – I’m now just wondering, in contrast to these, if there’s ever been a disaster situation where you haven’t gelled whatsoever with someone you’ve shot?

There were two instances. One was my fault and the other one, the person was nasty. That was Chuck Berry, the musician. He was awful and I couldn’t have cared less. I took two frames and he stood up and walked away. The other one, which was my fault, was with Nicole Kidman right at the beginning of her career.

She was famous for a movie called Dead Calm on a yacht. She was wet a lot of the time, so I wanted to do a portrait of her wet. I was in the darkroom working on prints and I suddenly realised that an hour and a half had gone by. So I went upstairs and they were just finishing her makeup, and they had done this heavy makeup. It was a breakdown of communication with the makeup artist. Of course, it wasn’t the story at all of what I wanted. At that point the PR woman came to me and said, “We have to leave in 20 minutes.” So I ended up with Nicole Kidman and the whole idea was to spritz her with water. With this heavy makeup, the spritz of water made her look like the Wicked Witch of the West!

Kaos is published by Taschen and available to order here