The Politics of Panniers: London Designers Channel Marie Antoinette

Anders Christian Madsen reviews the third day of Spring/Summer 2026 shows at London Fashion Week.

Coinciding with London Fashion Week, the V&A just unveiled an exhibition tracing the life and style of Marie Antoinette. Among its treasures are an extravagant antique gown with huge panniers inspired by the wedding dress worn by the young bride, and the bloodstained blade that was supposedly used to guillotine her in 1793. Those two artifacts illustrate the lesson historically represented by the iconic queen: pride comes before a fall. As pannier upon pannier swanned down the runways on Sunday at the London shows, you wondered what the designers were trying to tell us.

“I just feel like we’re all really on show,” Simone Rocha said after a collection that dealt with a girl’s discovery of dressing and the way we eventually form and construct our looks. She emphasized the crinolines that typically underpin her constructions, placing them under delicate fabrics that underlined their space-taking oddity, cleverly transforming the pannier from obtrusive to naive. Citing the debutante as a source of inspiration, Rocha spoke about the contemporary culture of “being performative, being on display.” From tiaras to bows, the designer drew on the tropes of the debutante but offered alternative, gentler ways of wearing them. (Her boys in tiaras were particularly poignant.) Rocha’s social commentary expanded with vinyl coats inspired by the plastic cases you get corsages in for prom: “The idea of something real being suffocated by something fake.” In another century, Marie-Antoinette— the trussed-up teenage queen—could relate.

SIMONE ROCHA

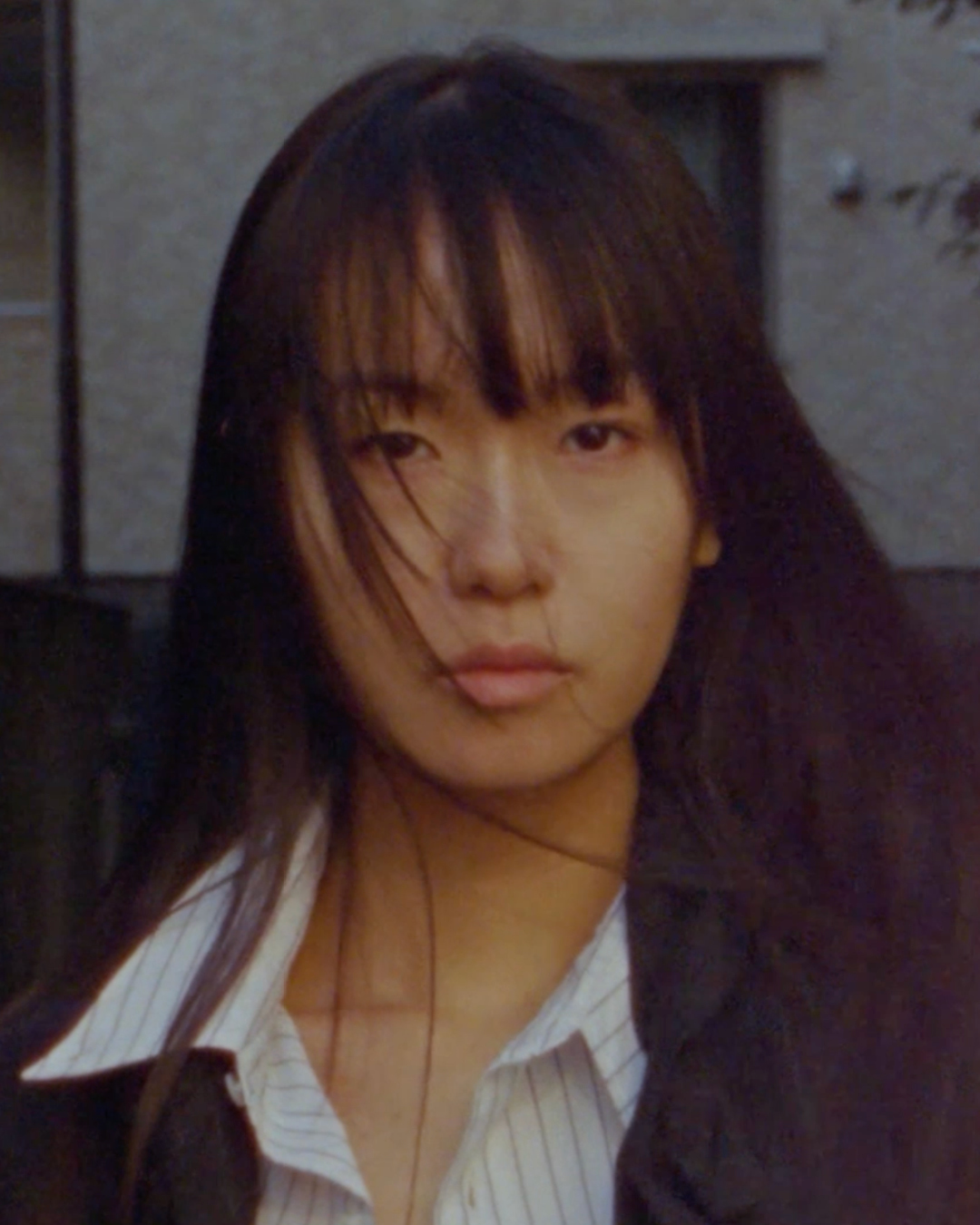

The rise of the pannier is no doubt connected to the corset. Its comeback over the last few years has been embodied by Kim Kardashian, who takes cinching to new dimensions. One of the star’s favorite young designers is Dilara Findikoglu, who closed the Sunday shows with a theatrical staging that cemented her mounting status as a designer phenomenon. In a pub minutes before the show, as hordes of black-clad fashion pseudo-goths shambled toward Ironmonger’s Hall, the bartender asked us if a rock concert was taking place. Presented on a cast that included Naomi Campbell and Amelia Gray, Findikoglu gave her following all the ripped-open corsetry, bondage straps, ball-and-gags and spike studs they came for, but in this designer’s world, things aren’t what they seem. Driven by feminist philosophy, the Turkish-born Londoner uses images of constraint as a way of taking charge: claiming the keys to the cage that many of her design elements have historically represented.

At Erdem, female empowerment was also at play. The designer shone a light on Hélène Smith, the late 19th-century Swiss artist and medium, who “would go into catatonic trances and draw what she saw,” as Erdem Moralioglu explained backstage. A psychologist divided her trances into three romantic cycles: sometimes she’d think she was at the court of Marie-Antoinette, sometimes she’d think she was a Hindu princess, and sometimes she fancied herself an alien from Mars. Smith even devised a Martian alphabet that was embroidered on looks in the collection. Moralioglu drew on the trances as a way of traveling through time and space, allowing her various embodiments to inspire shapes, colors and adornments. A nod to Marie-Antoinette, Erdem’s corsets and panniers cut a politer alternative to Findikoglu’s fetish ball, although the space-taking rigidity of his architectonic dresses was—converted to real-life dressing—just as impactful. You’ll need a lot of real estate to dress for Spring/Summer 2026.

ERDEM

There weren’t any corsets or panniers in the Paolo Carzana collection, but his gauzy, ghostly expressions easily seemed like something out of an 18th century epic. Held in the British Library, his show was attended by Sarah Burton and Sir Paul Smith (whose foundation Carzana is a beneficiary of), which tells you something about the industry’s hopes for this young Welsh designer. In place of crinolines and cinchers, Carzana created a majestic silhouette through garments organically hand-dyed and gowned over the anatomy like dampened muslin. His elaborate dyeing processes enable the materials to become sculptural in form, which—alongside headpieces created by Nasir Mazhar, which evoked the ships Marie-Antoinette placed on her giant wigs—made the collection feel decidedly ancien régime. “I was looking at endangered and extinct animals as a source of inspiration, finding a way to honor something so precious in an abstract way,” Carzana said. “It’s a focus on the genius of Mother Earth and the monster of humanity.”

Perhaps his Weltschmerz served as an explanation for the arrogance and danger we relate to the 18th-century silhouette that was haunting the runways on the Sunday of London shows: mirroring the madness of our times—the greed, the vanity, the politics, the social media—in our evolving, exaggerated wardrobe desires; waists cinched and hips boned like some pleasure-seeking teenage queen from the 1770s. If it all becomes too much, take a breather with Emilia Wickstead. Presented in her store on Sloane Street, her breezy show took inspiration from Robert Mapplethorpe and the community that surrounded him, from Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen and Patti Smith. Through deconstructed shirts, hand-painted florals and a push for denim, Wickstead explored new and more down-to-earth proposals for the classic suit. “We’re normally quite buttoned-up and perfect,” she said, gesturing at silk garments that had been purposely creased. Her show was a nice interlude amid a day of courtly constructions.