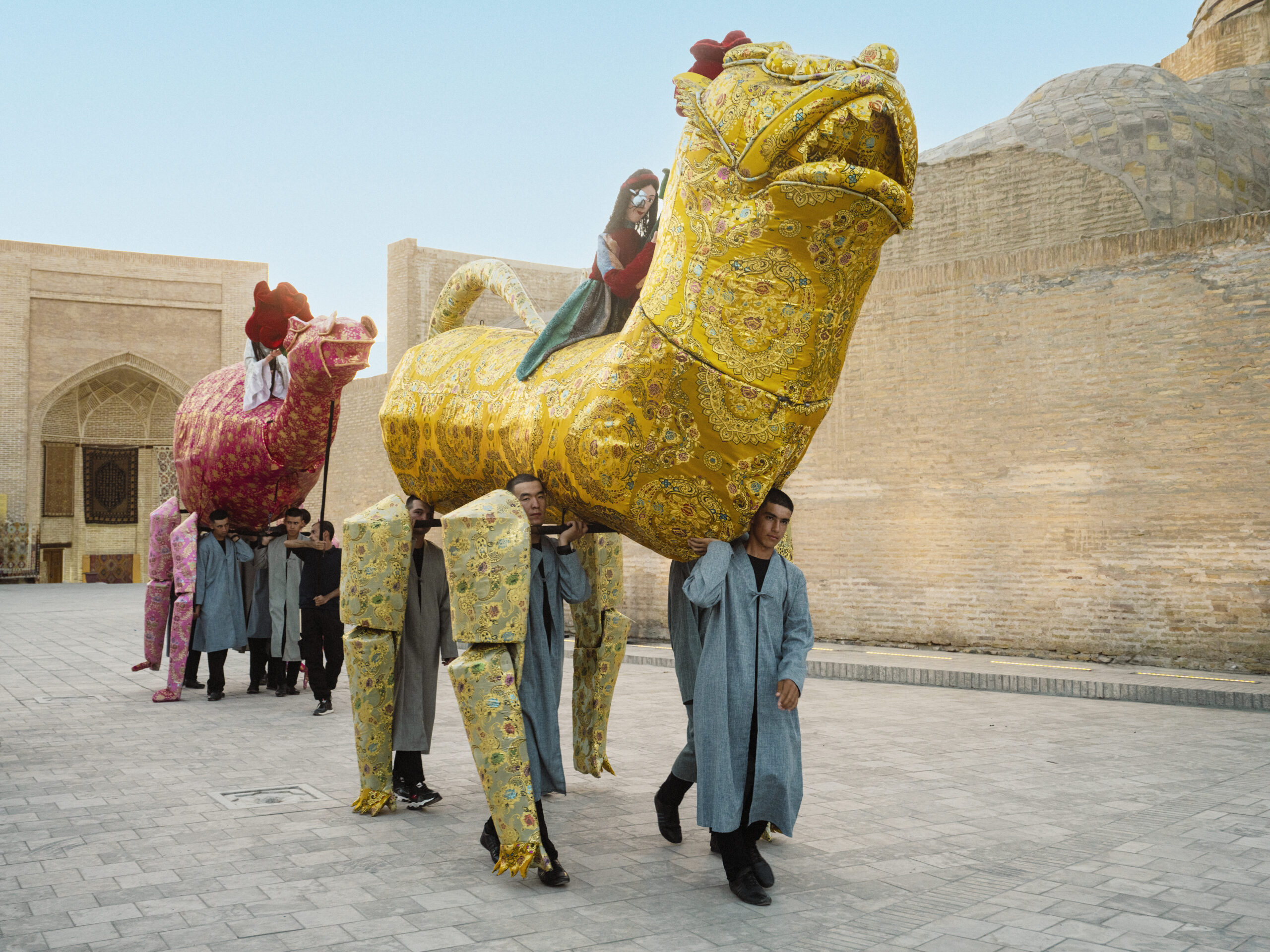

UNTITLED, 2024–2025 BY MARINA PEREZ SIMÃO IN COLLABORATION WITH BAKHTIYAR BABAMURADOV. PHOTO FELIX ODELL COURTESY OF THE UZBEKISTAN ART AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION

Reborn Through Art: Past and Present Intertwine at Uzbekistan’s Bukhara Biennial

Recipes for Broken Hearts opened this month. EE72 Contributing Art Editor Dominique Heyse-Moore takes us inside.

In the corner of an old caravanserai — inns for travelling merchants — ceramic bird whistles called hushtak are piled. We are invited to play them, and after getting over our hesitation to touch the art, over a few days, our melodies are recorded into a collective soundscape, swelling the courtyard with a heartening chorus. This is David Soin Tappeser’s Mur-Mur. Two birds fly home with me to my children in London.

Bukhara, an ancient city in modern-day Uzbekistan, is building a murmuration of travellers, art and ideas through Bukhara Biennial, a ten-week contemporary art festival within the Old City, very freshly restored under architect Wael Al Awar. The first one, which opened this month and runs until Nov. 20, is entitled Recipes for Broken Hearts, obviously about history, but also grieving our contemporary global catastrophes.

Once on The Silk Road, the romantic imagining of the city is of sumptuous craft and cultural exchange, or the big history of the Islamic Golden Age, Genghis Khan and Soviet rule. We hurtle there by plane and taxi, searching for Wi-Fi; visits to ancient places often jar with the onslaught of modern life. This is faced head-on by bringing contemporary art (“rupture itself,” says Diana Campbell, curator of the first biennial) into the two-millennia-old UNESCO site. The mud city Bukhara has never been fixed for long, devastated and reimagined again and again.

SAFAR (JOURNEY), 2025 BY KAMRUZZAMAN SHADHIN IN COLLABORATION WITH ZAVKIDDIN YODGOROV. PHOTO BY FELIX ODELL COURTESY OF THE UZBEKISTAN ART AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION

(CENTER) BLACK BILE, 2024–2025 BY PAKUI HARDWARE IN COLLABORATION WITH ALISHER RAKHIMOV AND SHOKHRUKH RAKHIMOV AND (LEFT) ᠣᠩᠭᠤᠳ (ONGOD), 2025 BY NOMIN ZEZEGMAA, IN COLLABORATION WITH MARGILAN CRAFTS DEVELOPMENT CENTRE (ODILJON OKHUNOV, JAVLONBEK MUKHTOROV). PHOTO BY FELIX ODELL COURTESY OF THE UZBEKISTAN ART AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION

Lessons have been learnt from criticism of contemporary art biennials that dot the globe. At Bukhara Biennial, many artists are Uzbek, every artwork a collaboration with local artisans (given almost equal billing) and made locally; the heart of the public launch party is generous mountains of the national rice dish, palov. The story goes that the dish was invented by philosopher Ibn Sina to heal a broken-hearted Prince not permitted to marry the daughter of a craftsman. “In that, I had everything I needed,” says Diana.

Recipes for Broken Hearts is entered through the Toqi Sarrafon, a trading dome once run by Jewish and Indian merchants, a far older market system than contemporary art. The chains of rooms around caravanserai and madrasas (a form of school) adapt well to exhibiting art, from films to mosaics. Walking the historic Shakhrud Canal, Longing, a boundless ikat weaving by Hylozoic/Desires, traces the disappearance of the Aral Sea (think ancient loom meets satellite imaging).

The piece Gavkushon Madrasa is conceived as a ‘house of softness’ in response to violent history and here Bahamian artist Tavaras Strachan works poetry by Langston Hughes, written in Uzbekistan in the 1920s, into silk rugs handwoven with local and West African symbols by Sabina Burkhanova. Global systems of power are marked and resisted. Nearby, I purchase a carpet with unmistakably Bukharan horse motifs woven around the 1920s: first customer of the day, the back of the tiny shop is opened for me to see a large sunny weaving school.

THE OBSERVER’S ILLUSION, 2025 BY RUBEN SAAKYAN IN COLLABORATION WITH KONSTANTIN LAZAREV. PHOTOS BY FELIX ODELL COURTESY OF THE UZBEKISTAN ART AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION

The ruin of Khoja Kalon Mosque, built 1598, is the most impressively conceived succession of artworks. Entered through Colombian artist Delcy Morelos spice-laden woven pyramid we are wrapped in sun-warmed cinnamon, cloves and turmeric and move blinking into the starkness of Antony Gormley’s monumental piles of 200 mud bricks – the adobe material of Bukhara – beyond which dunes obscure a desert garden by Ruben Saakyan.

My carpet and metres of ikat silk woven in the Ferghana Valley fold into tiny parcels, reminding me that these technologies were conceived for travel. I fold myself into the plane and watch the Uzbekistan Airways flight safety film, where seatbelts are fastened along camel trains, warriors take the brace position and merchants stow their goods overhead. Uzbekistan sees no reason for a rich past not to be woven with ambition for the future.

The Biennial and restoration plan is commissioned by Gayane Umerova, who heads up Uzbekistan’s Art and Culture Development Foundation.

Dominique Heyse-Moore is Senior Curator of Contemporary British Art, Tate.