Fendi’s Childlike Couture

Anders Christian Madsen

reviews the Fendi Spring/Summer 2026 collection by Silvia Venturini Fendi.

This season, some fourteen new designers are entering old fashion houses. They’re tasked with interpreting and (most importantly, for the owners) honoring the heritages of the institutions to which they’ve been handed the keys. Silvia Venturini Fendi has always had the keys to her house. Last season, after the exit of Kim Jones, she automatically resumed creative director duties the way she did when Karl Lagerfeld died. Then, as now, every time she steps up to the plate—always without the industry hysteria that surrounds other designer firsts—she instinctively and graciously creates collections that tick all the boxes of the reverence and evolution expected from a new designer. This isn’t just because Venturini understands the house that carries her name, but because she’s good.

After taking up the mantle again last season, on Wednesday afternoon, she proved that fact once more with a considered and at-times ingenious collection that felt inherently authentic to the Fendi she knows by heart. “I wanted to do something romantic in my way. Something that talks about kindness: sweet and soft as opposed to strong,” she said before the show. Assuming a childlike spirit we could all do with in this age of antagonism, Venturini evoked a couture-like silhouette by adapting the adjustable functions of children’s wear into sporty and elegant garments. Literally, jackets, tops, skirts, and trousers were fashioned with zips and pullers like those of hyper-practical clothing for toddlers, used to cinch and sculpt and create the volumes we associate with the language of couture.

FENDI

FENDI

The collection was presented in a set designed by the artist Marc Newson—who is married to Charlotte Stockdale, who styles the Fendi women’s collections alongside Katie Lyall—which he described as a “patchwork quilt.” Covering the headquarters’ sprawling runway floor, squares in different nuances of color were repeated in the large conversation sofas that filled the room. Venturini didn’t say it—maybe because the impact was inadvertent—but it felt like an abstract idea of the interior of a home; a feeling that only contributed to her deep-rooted understanding of Fendi as her family’s house rather than a brand. On this sea of color, she sent out childlike floral patterns, filtrage garments that kind of felt like advanced versions of kids’ raincoats, and Lego-like, naive patterned fur achieved through painstaking techniques.

Asked what inspired the childlike angle, Venturini didn’t cite the political climate, but something closer to home; closer to Fendi: “I have a big family, and Delfina is expecting another set of twins,” she said, referring to her daughter, who already has three children. “So, we got to five, which is an important number in my family.” (Her grandparents, the founders of the house, had five daughters.) Had Venturini found inspiration for her notion of child-to-adult dressing in observing how her eldest granddaughter, who is eighteen, experiments with clothing? “She knows what she wants,” she smiled. “She lives in New York, but she’s put the alarm clock on to wake up and watch the show. She’s the first judge. I’m in trouble when she calls.”

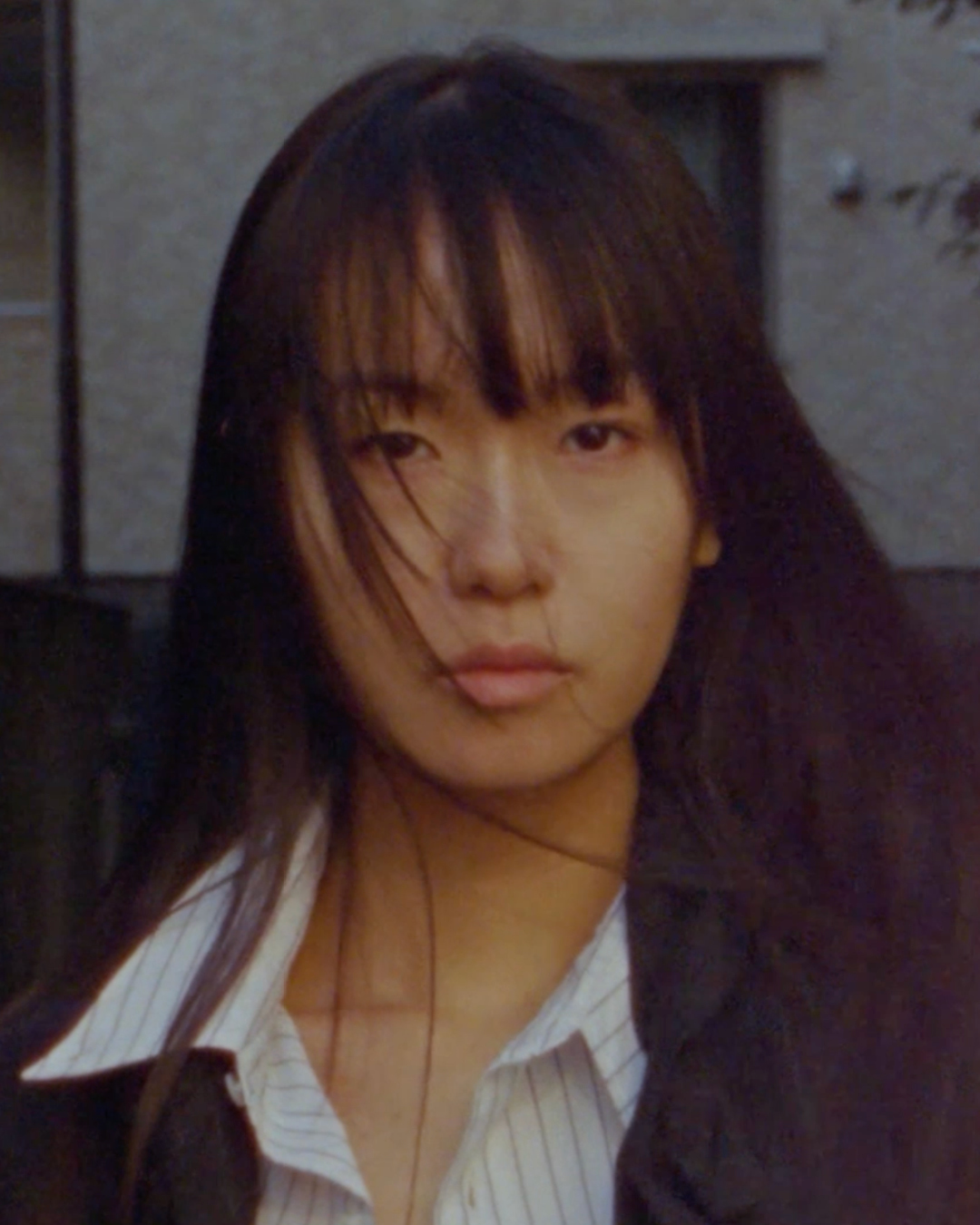

We’ll await her granddaughter’s judgment on this fun-filled collection, whose colors, floral patterns, and holographic effects weren’t for the faint of heart. But as Venturini knows best, Fendi was always about a bold proposition. It’s unafraid and lighthearted; never a wallflower. If she was seeing the world through the eyes of a child—yet to be tarnished by the pessimism that comes with adulthood—she emphasized the message in a cast that included some of the biggest character models in the industry. Mariacarla Boscono, Karen Elson, Adwoa Aboah, Leon Dame, Clément Chabernaud, and Gabbriette Bechtel were just some of the names that joined an ensemble, which—crucially for the childlike premise—included models of all ages.