The King and I: In memory of the late Giorgio Armani

He was the richest designer in the world. She was one of the women closest to him. Giorgio Armani’s Global Communication Director, Anoushka Borghesi, reminisces about her life with the legendary designer.

Anoushka Borghesi was 32 when Giorgio Armani summoned her for an interview. “It was June 2010 and I had never been more scared to do an interview. They also created this atmosphere: first, you’d wait in one room, then in another room, and the tension grew. I walked into the office at Via Borgonuovo, Milan, and he was sitting there with my CV on his desk. He looked at it and went, ‘Ah, Yves Saint Laurent? Ten years? Not bad.’ He appreciated loyalty and longevity; that somebody hadn’t gone around the houses. My voice was trembling… The effect he could have with his gaze and the distance he would create between himself and others. I wasn’t sure I wanted the job, because the feedback I got from the press in the UK at the time was that ‘Armani is tough.’ It wasn’t an easy company. The job was for Emporio Armani as Head of PR. After the interview, they called me and said, ‘Mr Armani wants you to have the Giorgio job.’ It made me aware of how he saw me; that he was going out of his way to give me something special.”

Five weeks after the death of Giorgio Armani, his communications director is taking her first weekend off after an emotional and intense month you could only liken to the passing of a monarch. In Milan, she orchestrated his memorial and commemorative shows, remaining poised as ever in her black Armani suit and her mid-length blonde hair lightly teased the way he preferred it. Receiving mourners, she was warm but authoritative, living up to the image she has gained in the industry as Armani’s charismatic publicist since 2010. As Borghesi exhales for the first time since the death of her beloved boss on September 4, we meet in London to reminisce about her life with the designer legend.

“I wore an Yves Saint Laurent semi-sheer dress to the interview. Navy blue, obviously. It was very Armani but a bit edgier, and I wore it with heels that weren’t too high, which he wouldn’t have liked. At the time, Armani was very far from my aesthetic. I was young, and you need to have a maturity as a woman to really love it. I wasn’t confident enough to wear it. The one thing that changed drastically after I got the job was my hair. I went in with a long, blonde, shaggy mane. He never said anything but I could feel it wasn’t right. So, I cut it into a Tilda Swinton crop… which he did say something about: ‘Anoushka, you look like an istitutrice tedesca!’ (A German governess.) “He wanted it more feminine, so he did forge my haircut to become a bit longer and wavier. He always had a lot to say. Once I came in wearing a Perfecto [jacket]. He said, ‘Why are you wearing that?’ He said, ‘Anoushka, don’t wear something because it’s trendy.’ And he was right. He really changed me. He had a big impact on me.”

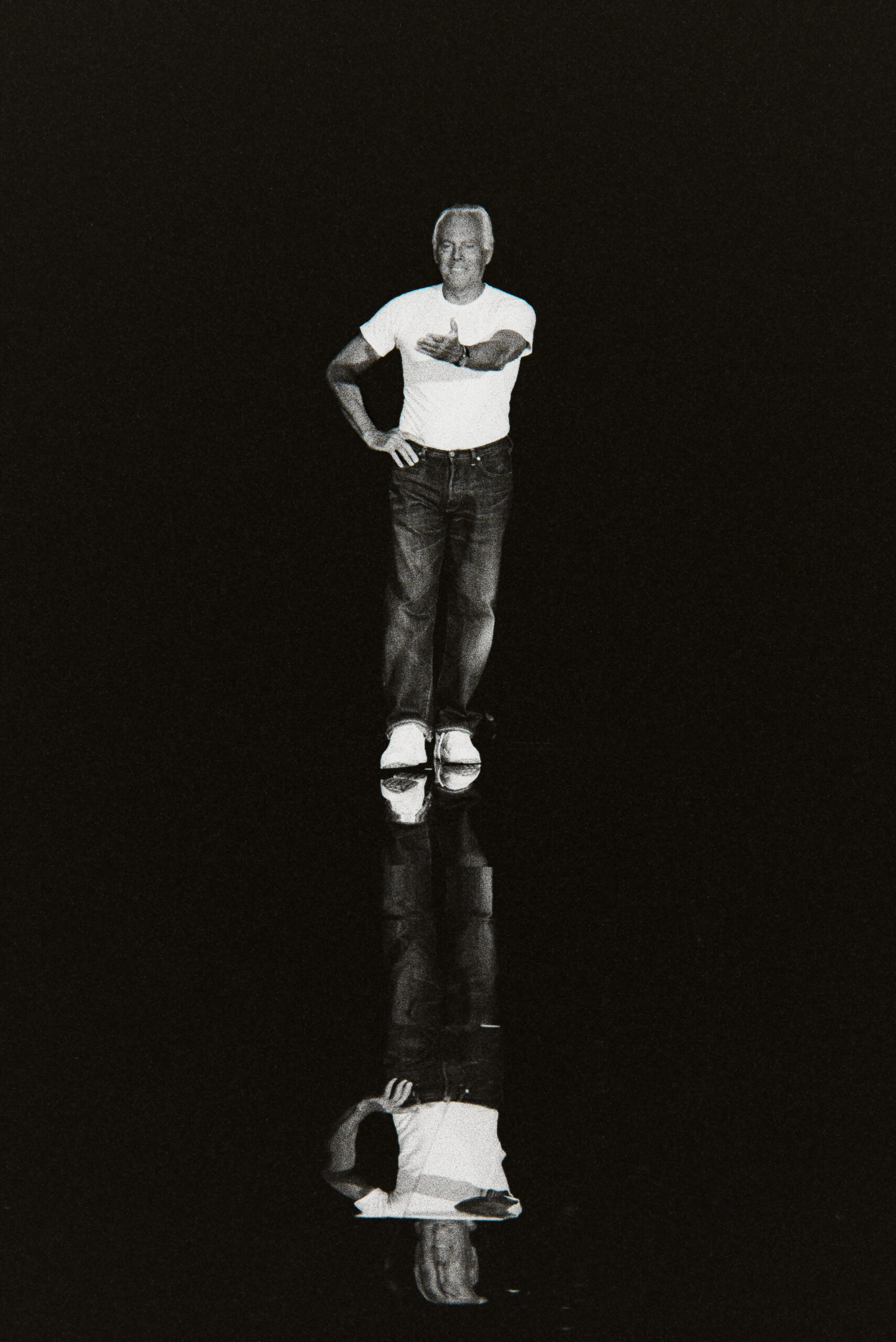

PHOTOGRAPHY ROGER HUTCHINGS

In 2010, Borghesi had spent a decade working in public relations for Yves Saint Laurent, building a career that began with a student job for the house during her studies at the American University of Paris. She had landed the gig on the heels of an internship at Gucci—whose owners bought YSL in 1999—where she had quickly risen through the ranks, thanks to her professionalism and fluency in four languages. A product of a late-1990s fashion world ruled by Tom Ford’s sexy coolness, a career with Armani wasn’t on the cards. But she soon discovered a chemistry she couldn’t deny.

“He loved an English accent. His previous PRs had had one, from Noona Smith-Petersen to Isabel Clavarino. He always wanted me to speak English, even if he didn’t fully understand. I think he realized that he could use me because I spoke to the people, and he didn’t have many relationships with the press. He recognized that I could help him translate something. He wanted me to sit next to him in his interviews. In meetings of ten people, he’d look over and just catch my eye. He knew how to pull you in. He’d had this pattern with Isabel and Noona before me. I wonder if he felt differently with women by his side than with men. The fact that he recognized me like this made me very dedicated. The first two years were incredible. I didn’t see his hard side yet. That came later.”

He wanted me to sit next to him in his interviews. In meetings of ten people, he’d look over and just catch my eye. He knew how to pull you in. The fact that he recognized me like this made me very dedicated. The first two years were incredible.

Anoushka Borghesi

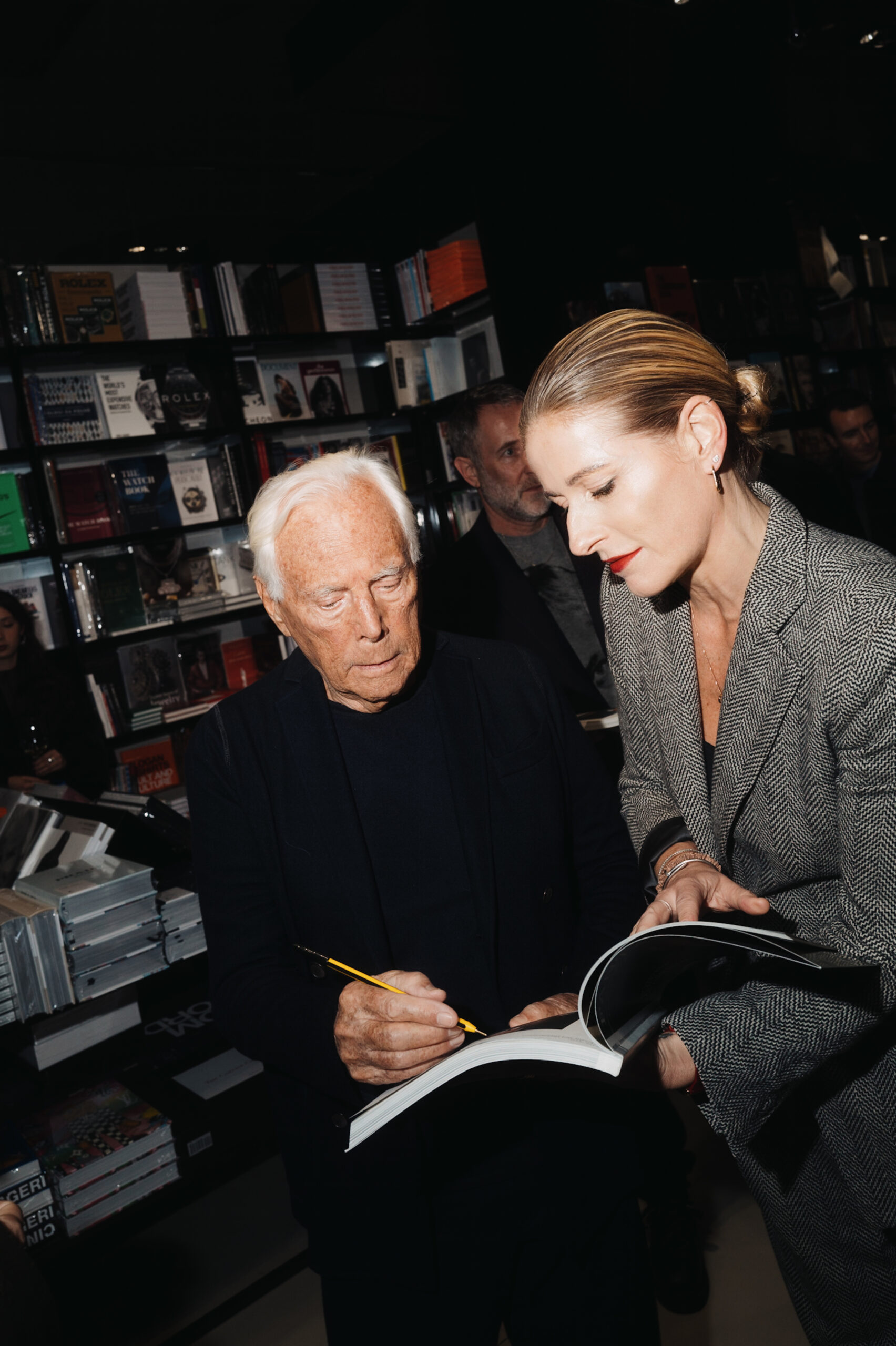

PHOTOGRAPHY LUCAS POSSIEDE, ARMANI SIGNS COPIES OF A MAGAZINE ALONGSIDE BORGHESI IN NOVEMBER 2025.

Born in England in 1978 to an Italian father, who worked at the Dorchester, and a German mother, who worked for Air France, Borghesi spent the first 10 years of her life in Richmond before her family relocated to Tuscany, where much of Italy’s fashion industry is based. As a teenager, she obsessively read Vogue and Marie Claire. A year after the move to Tuscany, she lost her mother to cancer, a trauma she says instilled in her a sense of strength and adaptability that would become vital tools in her relationship with Armani.

“In the beginning he was testing me a lot. I think he was scared I’d leave, because he’d been betrayed many times and it was hard for him to build trust. He hardly ever said ‘well done’ for anything. That wasn’t in his vocabulary. Every Monday I would get a call if he hadn’t been featured in the weekend’s iO Donna, which is the supplement of Corriere della Sera: ‘Why are we not in it?’ He’d be really shouting. I’d say, ‘But Mr Armani, you can’t have the cover every week!’ It gets to you after a while. Once I said, ‘Mr Armani, it would be nice if you could sometimes acknowledge if I do something well.’ He said, ‘Anoushka, of course you’re doing well. Otherwise you wouldn’t be here. I’ve got a lot to do. I need to tell you what doesn’t work.’ I’m not someone who needs sugar-coating so once I understood that, I was fine. Things don’t stick with me. He noticed that. He said, ‘Mamma mia, you’re a pungiball!’” (Someone who easily bounces back.) “He enjoyed going against you. He’d build up your strength.”

Professionally and in private, Armani was a creature of habit. Because of his longevity and his astronomical wealth, he had been able to mold his surroundings to his image of a perfect world. Every space he created embodied his ideal fusion of Italian monumental modernism morphed with Japanese wabi-sabi, from his nine homes – in Milan, Broni, Forte dei Marmi, Portofino, Pantelleria, St. Moritz, Saint-Tropez, Antigua and New York City – to his army-green superyacht, his hotel franchise, stores and offices. As Borghesi discovered, his sense of curation also applied to the people around him.

“In the 2010s, I had a bit of a crush on Phoebe Philo’s work at Celine. There was this campaign with Daria Werbowy where she had no eye makeup on, just red lipstick. I thought, ‘I need to replicate that.’ One morning I was sitting in a meeting and he was looking over at me, and you could see there’s something bothering him. He said, ‘Err, uh, Anoushka…? What have you done to your face?’ I said, ‘Oh, um, I forgot to put mascara on…’ He went, ‘Don’t lie to me, you didn’t have it on yesterday, either. Stop doing it! You look like an embryo!’ He had very strong opinions. When you tell people, they say, ‘No, you can’t say that!’ But this was Giorgio Armani. If I’m not going to take a strong opinion from someone like that, who am I going to take it from? Of course, I kept my individuality, but a lot of his advice was on point. When I was younger, I could get a bit offended, but he was also very sarcastic. When you got to know him, you’d see he only said it to people he cared about.”

He had very strong opinions. When you tell people, they say, ‘No, you can’t say that.’ But this was Giorgio Armani. If I’m not going to take a strong opinion from someone like that, who am I going to take it from?

Anoushka Borghesi

Armani built his fashion empire against the odds of a poor childhood in the northern Italian town of Piacenza during the interwar period. His successes were, in large part, due to the military discipline and micro-management with which he ran his independent company, and the virtuous principles of simplicity that permeated everything he did. His day-to-day life was shaped by a routine that included a weekly meeting with Borghesi in which she’d present him with press proposals and new coverage.

“He liked things to be very simple. For lunch, his waiter from home would bring in cuts of kiwi, a coffee and water. It was tasteful but never extravagant. He was rich but you never felt it. He didn’t love people working from home. He expected us to be there, and he’d come and look for you. In meetings, he’d have a pencil and a stack of white, unlined paper that he would scribble and draw on. He wanted a clear agenda of what points I wanted to discuss with him. He would go mad if I said something that wasn’t on it. Paul Lucchesi, his assistant, was always there with a recorder, because Mr Armani never believed us if we said he’d approved something he didn’t recall approving. Once, he insisted he’d never approved something and it became such a big deal that we had to sit down and listen to the recording. I started getting worried that he hadn’t said what I thought he’d said, but when we got to it, he said, ‘Ah, vabene.’ He could get angry but it would pass immediately. He’d move on.”

While it could sound brusque, Borghesi thrived in the rigorous environment Armani created. If her efforts weren’t verbally acknowledged, the designer found other ways of showing his admiration for his protégé. In 2013, after three years in the job, he gave her the ultimate stamp of approval: Borghesi and her boyfriend were invited to join him and his family and friends—including his sister Rosanna, his nieces Silvana and Roberta, and his nephew Andrea—on one of their fabled summer vacations to his house in Pantelleria. For the next thirteen years, until Armani’s death, she traveled with him every summer, Easter and Christmas.

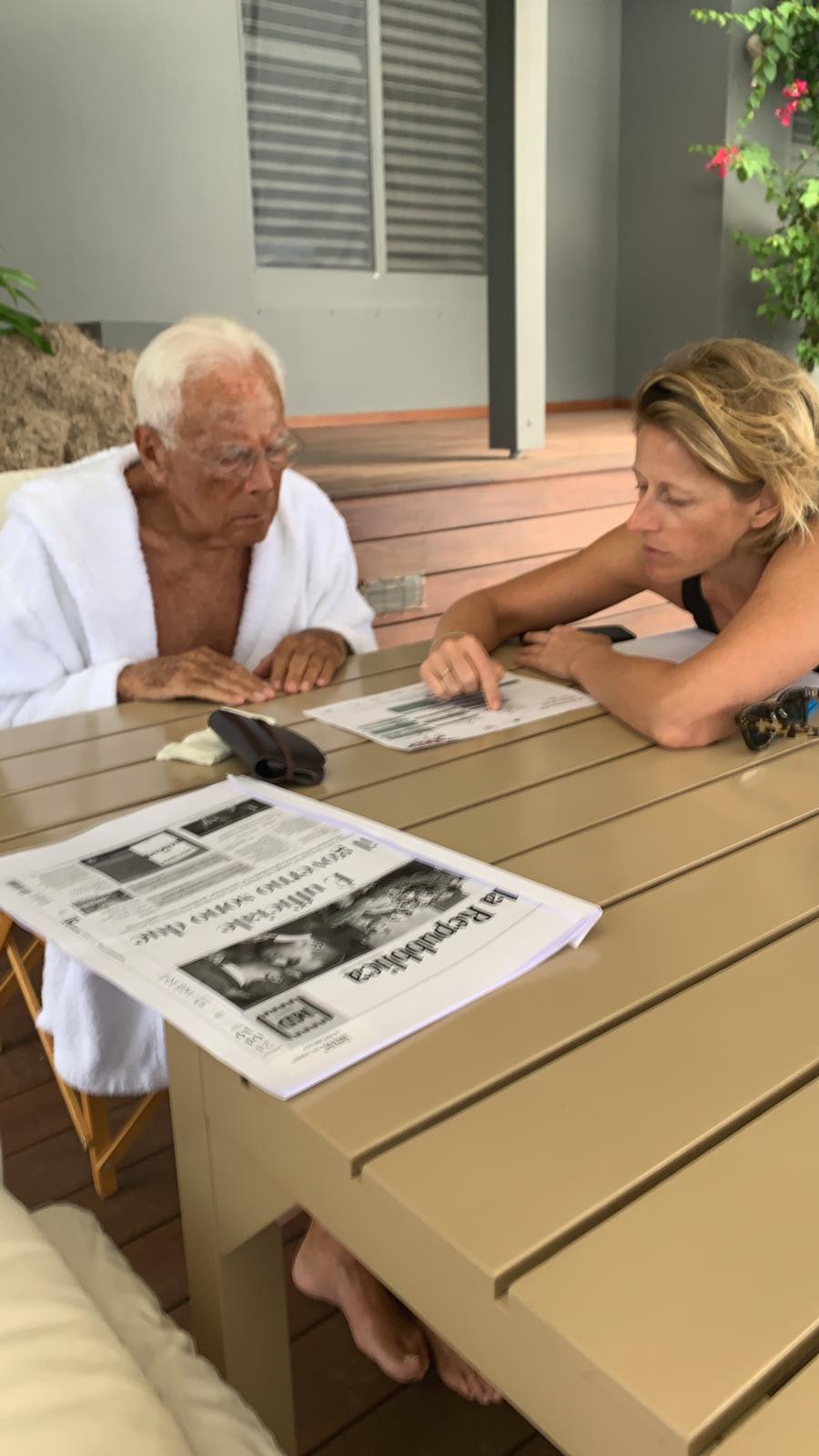

ARMANI AND BORGHESI ASSESS THE FASHION WEEK SCHEDULE AT HIS HOUSE IN ANTIGUA IN 2017.

BORGHESE TRANSLATES THE LATEST INTERNATIONAL PRESS COVERAGE TO ARMANI, ON BOARD HIS YACHT, MAÌN, IN THE SUMMER OF 2017

“The first holiday was a baptism of fire. I was worried. ‘What do I wear, what do I do?’ But funnily enough, I managed to be one of the few people who actually relaxed with him. I would read, I would be myself. It was good. In the morning, we’d go for a walk together but it wasn’t as if he was always around. He’d give you space. And I’d get my own holidays on top of it. The dinners could be very entertaining… his fights with certain people. He wouldn’t speak a lot but just say a few words and shut everyone up. There were certain rules, but I realized that the simpler you were, the easier it was. The first time I brought dresses that were too much. Linen would annoy him. He liked simple cotton. Some prints would annoy him. Once, I wore a flower print and he said, ‘Mamma, sembri una contadina toscana!’ (Mamma, you look like a Tuscan peasant.) “But I still wore it in defiance. Once, two of us wore stripes for dinner. He looked at us: ‘Detesto le righe!’ And we were like, ‘Half of your collections are stripes, Mr Armani!’”

Over the years, Borghesi and her boss ignited a chemistry that transcended their working relationship. She understood that his stern exterior and grumpy demeanor weren’t always to be taken literally. She got his sense of humor. She enjoyed his company, and he enjoyed hers. When the pandemic hit in 2020, she spent three months in lockdown with the then 85-year-old Armani in his house in Forte dei Marmi, strengthening a bond that only grew closer as he got older.

“People found it a bit weird that we had this relationship, but I wasn’t married and I had no children. I felt like home with him. In the later years, he would complain that I never invited him out. But it wasn’t so easy to say, ‘Mr Armani, let’s go out for dinner.’ I did in the last years, and that makes me happy. We’d go to La Pesa, which was the only place he’d go because he was used to the food. He’d have his risotto alla milanese. He was very quick. He never lingered. Then we’d go to the cinema. He loved films set during the war. Sometimes he invited me for dinner at home. He would ask a little bit about my personal life and what was happening in the world. He’d want to know about the other shows. There was a moment when I would tell him about what was good or cool right now, but I realized that wasn’t always a good idea. It was better to let him stay in his world.”

Despite his independent success, Armani remained competitive with peers and newcomers until the end. In the 1980s, his broad-shouldered tailoring had dressed a new generation of boardroom feminists, while his men’s tailoring had been a sartorial sex symbol. In the 1990s, Armani embraced a softer, more poetic expression conveyed in nomadic cuts and fluid elegance. Confident in his own direction, throughout the last two decades of his career he rarely veered from that aesthetic. For a designer so led by his own principles, the trend-driven culture of fashion wasn’t always easy.

“Miuccia Prada, I would say, was his biggest rival because he admired her for being so true to herself: for being the opposite of him style-wise, and being so loved by the people he wanted to love him. The complicated fashion ‘cool’ press loved Prada. They didn’t love Armani. He envied that. He wanted to have that, too, but he couldn’t because his style was different. He was too stubborn to change, but thank God he didn’t because chasing trends wouldn’t necessarily have been a success for him. He and Mrs Prada did send letters of admiration to each other, and that made me really happy. Saint Laurent he was very jealous of at certain times, especially during the Hedi Slimane era; again, because there was such a love for it from the insiders. He was even competitive with the people in Rome. He didn’t want to do events there. But even though he and Mr Valentino were massive rivals in their time, whenever he would call him, Mr Armani would be so happy.”

Miuccia Prada, I would say, was his biggest rival because he admired her for being so true to herself: for being the opposite of him style-wise, and being so loved by the people he wanted to love him.

Anoushka Borghesi

PHOTOGRAPHY STEFANO GUINDANI, ARMANI AND BORGHESI DISCUSS THE ABSENCE OF AN EDITOR BEFORE A SHOW IN 2011.

While Armani was confident in what his customer wanted and the company’s sales remained strong, Borghesi had to deal with a fashion press who often questioned the designer’s unrelenting commitment to the same style. When the oversized tailoring he popularized in the 1980s came back in fashion in the 2010s, every designer in the industry seemed to be referencing Armani, except for Mr Armani himself.

“He would simply say, ‘Every brand is doing those suits now. Why would I do them? The high street is copying me. I need to do something different for the clients who already have those things in their wardrobes.’ Now, I get it, and I don’t think I’m brainwashed to say so: you can go to Armani to find those suits, but he doesn’t need to put them on the runway. No creative wants to look back. He said, ‘Women have become tough now. When they needed suits and shoulders, it was because they needed to become stronger. Now, women need softness.’ And, you know, the collections were selling. But he was very aware of relevance, and the more he became aware of it, the more he would insist on staying true to what he wanted to do. He insisted on doing the show styling himself, down to the makeup. He said to me, ‘Anoushka, there’s nothing that makes me happier than putting the clothes together.’ How could I take that away from him and put a stylist in?”

Symbolized by the imperial eagle that hovers over his logo, Armani was an absolute monarch. The decisions that shaped his success were largely made in solitude by following his own instinct, with the exception of two key advisers: his partner in life and business, Sergio Galeotti, who died in 1985, and his head of men’s design Leo Dell’Orco, who remained his closest friend until the end.

“Because he was alone since he was 40, leading his company, it wasn’t always easy for him. He talked about Sergio who was Tuscan like me. We have a certain flamboyance and directness. He’d say, ‘You would have loved Sergio. He had so much charisma.’ But he rarely talked about that side of his life. He was very elegant about it. He was discreet, as you would be as an older man. But he was flirty. Ooh! Even with women. Whenever I was single, he liked to show me how you could attract the attention of a man. And it was kind of incredible to see the power he had. He did say he loved women, too. In a way, his sexuality wasn’t so defined. When it came to his friendship with Leo, one couldn’t live without the other. It’s tough for Leo now. They couldn’t go a day without speaking to each other. They were complete opposites. Leo is always happy and smiley. He has the energy that maybe Sergio had.”

In August this year, as his health was deteriorating, Armani canceled his holiday in Pantelleria, insisting that Borghesi, her boyfriend and her boyfriend’s children take his house instead. She video-called her boss every day from the island, checking up on him and showing him how tall his palm trees had grown. At Easter, she had joined him and his sister Rosanna in Saint-Tropez for what became their last trip together.

“It was the warmest he’d ever been. The two together are the most incredible. I felt so privileged to be able to sit with them as they reminisced about their childhood. It was sweet to see the bond that they had. What I realized in Saint-Tropez was how much he revered his father. He was very close to his mother but his father was always closer to his brother and sister. He always felt, perhaps, not good enough in his father’s eyes. He wasn’t as tall as his brother. His brother and sister were more extrovert than he was. But that’s what made him. That’s why he had the need to prove himself. I told him, ‘If your dad saw you now, he’d be so proud of you.’ I think he felt happy at the end that his dad would finally have been proud of him. The last time I saw him was three days before he passed. As I left the room, he looked at me and gave me a wink. That’s my last memory of him. It still feels like he’s present now.”