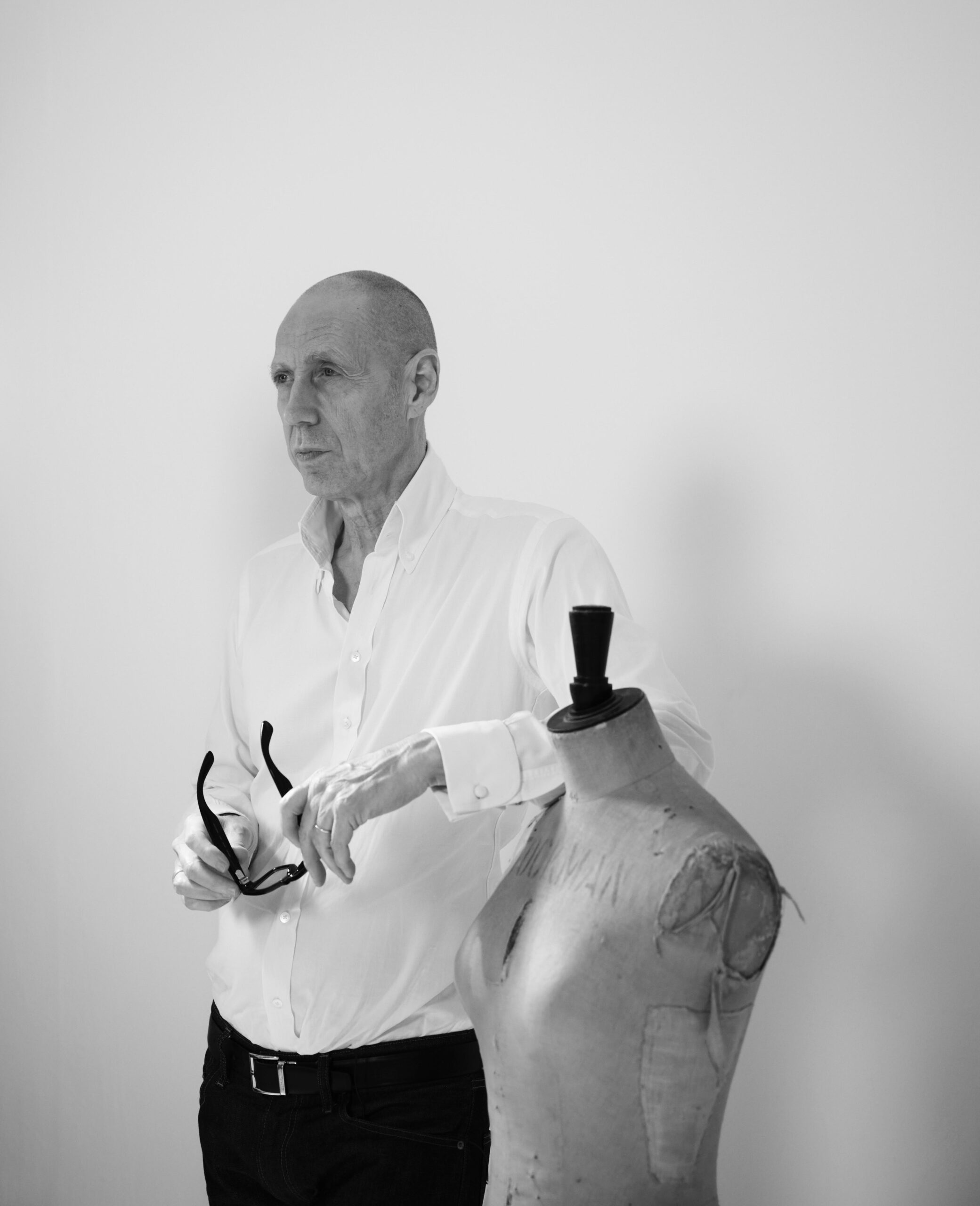

Nick Knight on 25 years of SHOWstudio

Photography Nick Knight

As SHOWstudio turns 25, Nick Knight reflects on experimentation, impermanence, and the technologies reshaping modern image-making.

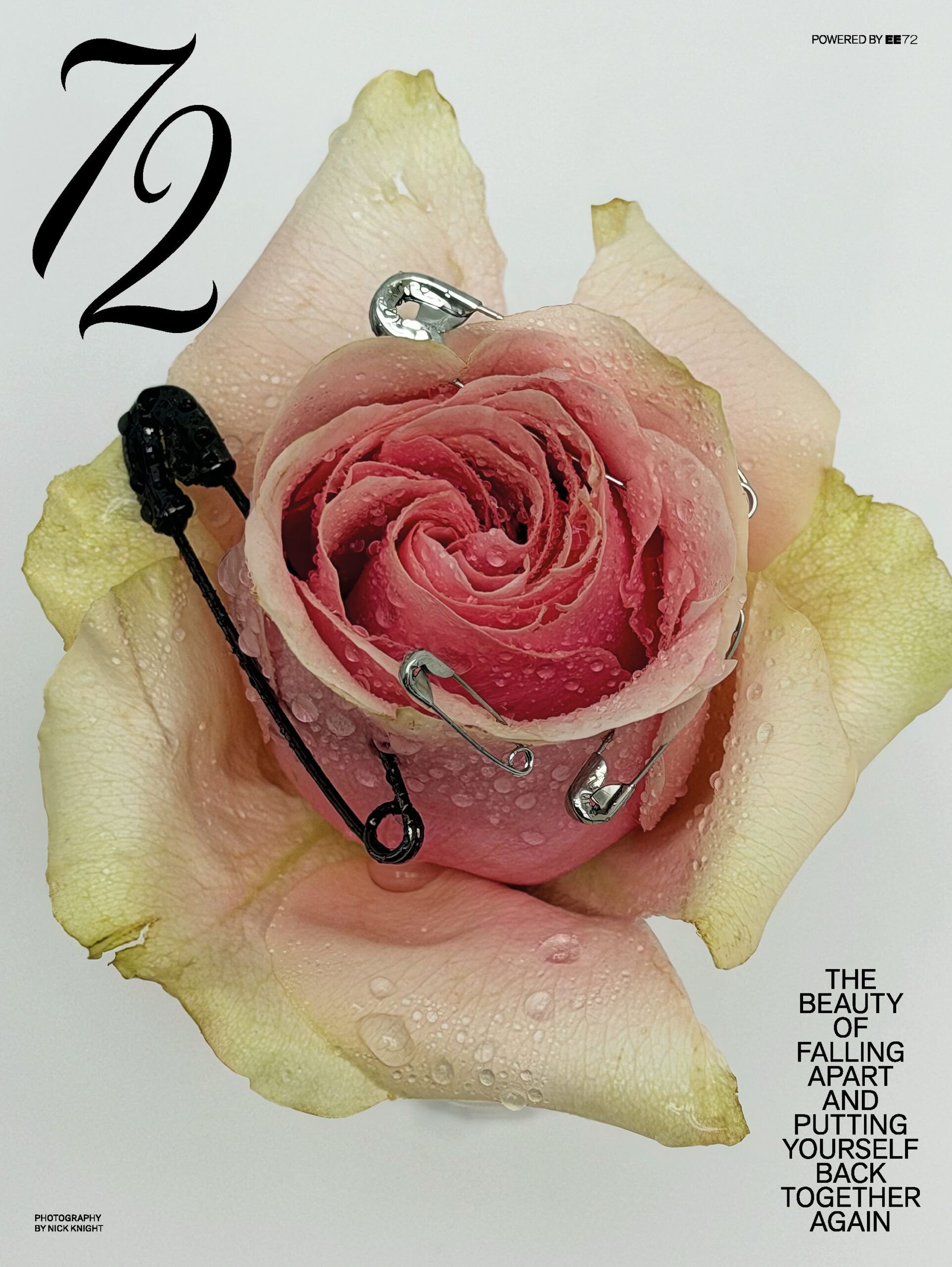

For the second issue of 72, two covers were produced: one, a portrait of a model (Ajus Samuel, photographed by Dan Jackson); the other, a single rose pierced with safety pins.

To admirers of Nick Knight, the latter will be instantly recognizable. Over the past decade, roses have become a recurring preoccupation in his work. Sometimes rendered in forensic detail, at other moments warped into glitching fields of color, the photographer treats them with the same reverence he applies to fashion. Like clothing, flowers can be both simple, beautiful objects and conduits for deeper meditations on time, impermanence, and decay.

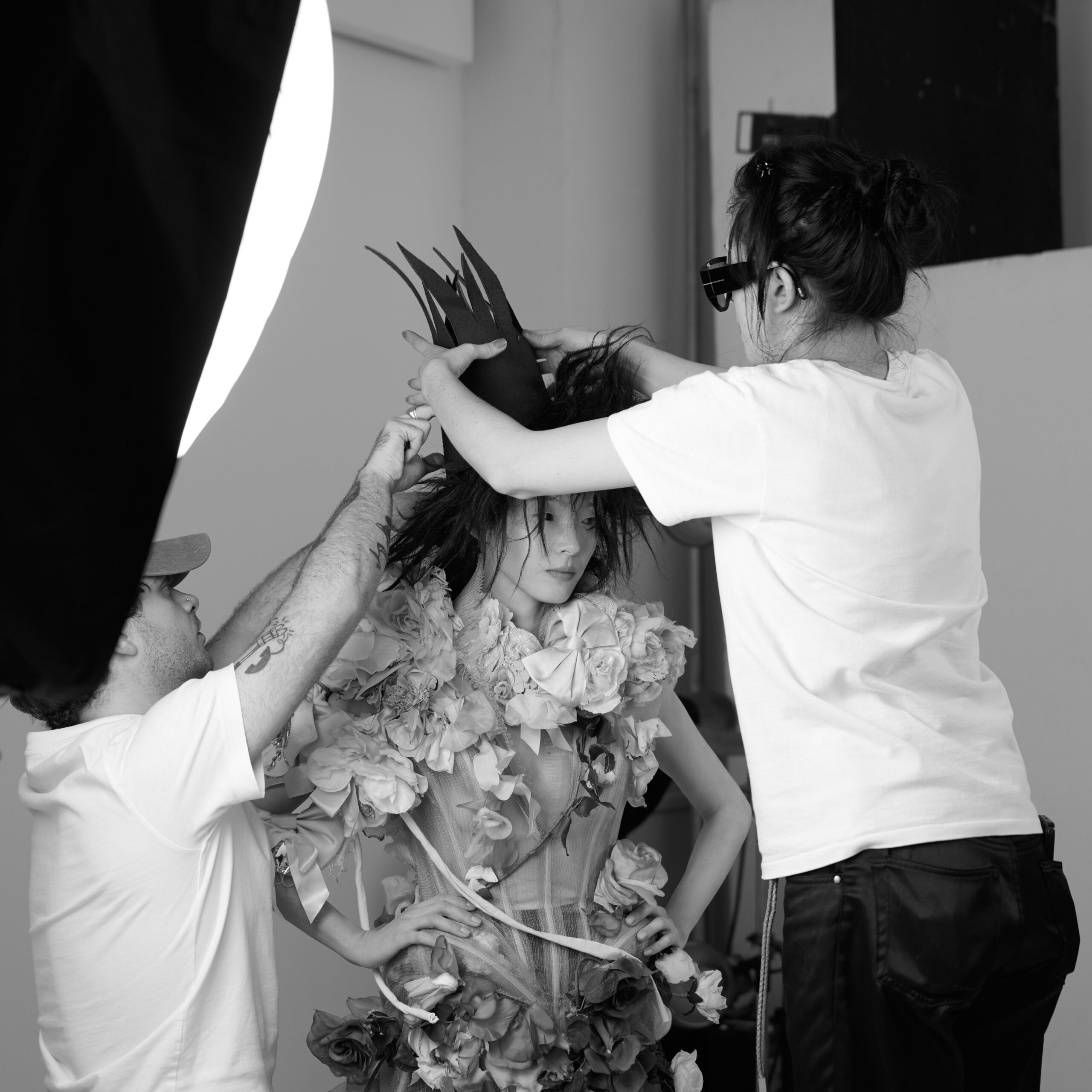

When we speak, Knight is in the midst of preparations for the anniversary of SHOWstudio, the platform he founded in 2000 that pioneered fashion film as a medium. Their latest film, NATURALLY, shot entirely on Ray-Ban Meta glasses, is another example of his long-standing commitment to working at the edge of whatever technology is available to him.

It is this outlook that makes him a rare dissenting voice amid today’s pervasive anxiety around AI. “I’m not pro-AI, but I’m pro-experimenting, and that is surely what, as artists, photographers or wider, we should be doing,” Knight says. “If we look back at the pioneers of photography, the people who shaped the medium they love, those were people who were experimenting with new technology.”

I’m not pro-AI, but I’m pro-experimenting, and that is surely what, as artists, photographers or wider, we should be doing.

Nick Knight

NATURALLY BY SHOWstudio MADE WITH RAY-BAN META 5

Before I ask you anything else, I wanted to mention the documentary Koyaanisqatsi. I watched it this week, and, to my surprise, as I was looking at your Instagram this morning I noticed that you recommended it to your followers. How do you and your work relate to this film?

The film I was introduced to by my wife Charlotte. Then my friend, Simon Foxton, was very much taken by it, too. I think it shows the different levels life exists on, from the molecular right up to the cosmic, through all the humour. I think it relates to my work because I’m interested in many, if not all, aspects of civilization and culture and humanity and spirituality as it goes. I started my career as a scientist. I wanted to be a doctor, so I tend to approach my visual communication, my photography, with a slightly analytical scientific approach. The first step is usually to try to find an answer, a solution, or a way of understanding things. So Koyaanisqatsi shows a beauty in science as much as a beauty in humankind. I’m a great believer in humankind as it goes.

It made me feel a mixture of optimism and fear. A feeling that we will always keep pushing forward – humans always have, always will. Which brings me to AI. There’s a lot of pessimism and fear around it in the industry, but you’re someone who seems to perceive it in a different way.

I think there’s a lot of very understandable fear. There is a fear of the future and a fear of change, which is innate as a species. However, I think it’s something that artists really need to be involved in because it’s happening and it’s going to go further and be developed even more. Artists need to have a big say in how it’s developed and what the new world shaped by AI looks like, because otherwise you have the military and big business, so greed and killing, shaping our future world, and that is what shaped our past world, and that has not gone that well.

Is there anything about an earlier era of photography that you find yourself missing today?

Do you want to go back to the point where you went to a Victorian photographer with a plate camera to have your picture taken that way. No. You can take your picture with your iPhone now and publish it to a worldwide audience. You don’t have to go through a magazine and say, can I publish this on your cover or can I put this in your magazine, and the person who owns the magazine says yes, you can, because it will make me more money, or no, you can’t, because it will put off some of my advertisers. So you are in a better position than you were even 20 years ago when the internet first came along.

With all these changes accelerating in the industry, what advice would you give to a photographer starting their career at this precise moment?

I wouldn’t look at your life as a career. Your photography is just a reflection of your life. It’s your desires and your feelings. If you call it your career, you are already basing it on the idea of making money, and I think that’s a mistake, because then you’re already looking at yourself as a commodity, not as a person. When people are starting out, they’re going to want to know how they’re going to put food on their plate and a roof over their head. There is some reality in terms of the money you might make from it. But I think if you are excited about life and excited about the possibilities, you don’t want to limit yourself by being scared of new technology or new ways of working. You shouldn’t take established values as things that you have to adhere to. You’re a new person in a new world. You can change the world how you want, but you can’t if you start to look at the past and use that as your defining criteria for the work that you do.

I think if you are excited about life and excited about the possibilities, you don’t want to limit yourself by being scared of new technology. You shouldn’t take established values as things that you have to adhere to. You’re a new person in a new world. You can change the world how you want.

Nick Knight

You recently shot the cover for the second issue of 72. Can you tell us about the process behind this image, as I know it was shot on an iPhone?

Yes, I have a daylight studio, so I just put the rose on a table. I asked my assistant for two or three safety pins, and stuck them in the rose. Ten minutes later, Edward [Enninful] had the picture on his phone. That was how it happened, shot on my iPhone, instantly, with daylight.

Roses have been a feature of your work for some time now, it must be second nature.

There is a story of a very great painter who has been commissioned to paint a dove, and then the client comes back months later and says, where is my picture, and the painter does it for him in two seconds. He looks baffled, but then realises that the painter has spent the last six months learning how to draw a dove.

Back in 2000, when you started SHOWstudio, what did you think you could do that no one else was doing at that time?

I’m not sure where the idea came from. Somebody remarked to me back in the 1980s when I was photographing Naomi Campbell, it’s a shame nobody else can see this happening. I was photographing her for Yohji Yamamoto. She was wearing a beautiful scarlet coat by Yohji and listening to music by Prince. There was me, the hairdresser, the makeup artist, my assistant, and the art director Mark Ascoli. It was a piece of fashion theatre or contemporary art, but only five people were witnessing it. As soon as I saw the internet, it became obvious that here was a developing new medium where you could eventually put short bits of film, to show clothes in movement and get those to an audience that was not able to see them normally.

Looking back, was there anything else that informed your decision to launch SHOWstudio?

I also thought, I don’t want to make my art all the way through my life to make somebody else money. I know where I fit into that equation. I know I make money from doing stuff as well, but I didn’t want that to be the only reason I photographed something. I’m so in love with fashion. But the editorial slant of magazines were profoundly racist and misogynistic and unpleasant at the time. This was a time when there were virtually no models of colour being shown on the covers of magazines and in advertising. I didn’t want part of that. So why should I have to keep on working endorsing somebody else’s values that I fundamentally morally disagreed with and that were fundamentally not interesting compared to what was coming up on the internet.

Was there a point early on when it became clear that SHOWstudio was going to succeed?

Alexander McQueen’s Plato’s Atlantis was a huge watershed [moment]. We’d been working with Lee for ages saying, why don’t you put your shows live on SHOWstudio. Eventually he did with Plato’s Atlantis, which, so tragically, was his last show. Six million people tried to come [to the website] to see that show. That was unheard of. It really crashed the internet, and it showed all the CEOs and the industry that instead of showing your collections to 300 people who all look cross and bored, if you team up with the right people, in this case Lady Gaga, you are going to get through to millions of people. Those six million ‘Little Monsters’ that came to try and see the show suddenly realised who Alexander McQueen was.

And now, 25 years later, how are you celebrating?

For the next year, I have 25 projects which I am going to deliver to the world, as it were, which are all based on an initial SHOWstudio project. When we first started, we did a time capsule, a little box set, which we had, I think, 20 contributors in. We are redoing that box set 25 years later. We are putting out 100 boxes. Inside each box there are 24 artists, and then on top of that, you have one mystery guest taken from 100 people who have been on SHOWstudio in the past.

And then, of course, I also wanted to do a fashion film. I’m working on it with the Ray-Ban Meta glasses, because that’s a completely new way of working. We’re creating Gaussian scans with the glasses – basically a 3D scene. What you do is walk around your model, just looking at them and videoing that journey three times. Once you’ve done that, you put that data into AI, and you can recreate that scene in total three dimensions. This is a new physical way of creating an image. It looks like a John Singer Sargent pageant painting, or a Klimt, or one of the impressionistic painters. The texture of it looks like painting. It doesn’t look like tech in the cold Matrix way that we’ve been told to think tech looks like. It looks like little rips in the fabric of light.

It sounds beautiful. What do you think is the future of fashion film and photography?

The thing I’d like to finish on is that, we do not know where we are on the evolutionary journey. We don’t know if we’re at the beginning, at the end, or in the middle. There is a fairly arrogant assumption that this is as good as it gets in terms of evolution, whereas we know, when we look back at our path of evolution, we have only got to go back through a few million years to work out that we didn’t always look like this, and we were quite different life forms before. So, we have to take on these new things as artists. If we evolve into a new life form, which is silicon based, that’s evolution, and evolution always happens towards the better.

Trust in the Koyaanisqatsi of it all.

Yes.