Ben Whishaw on slow cinema, Queer art and the magic of Peter Hujar

Photography Tomo Brejc

Ben Whishaw gives a poised, poetic performance as photographer Peter Hujar in Peter Hujar’s Day, an unconventional biopic that unfolds as a meticulous, minute-by-minute account of one ordinarily extraordinary day.

On December 18, 1974, writer Linda Rosenkrantz had the inspired idea to ask her friends and peers to recount, in exacting detail, everything they had done over the course of a single day from waking to sleep. She sat down with artist Chuck Close and photographer Peter Hujar, speaking with them at length about every small, mundane detail of the previous day’s minutiae. The book project was never realised, its concept drifting into that vast archive of brilliant ideas left unfinished and forgotten.

Hujar would die of AIDS related pneumonia in November 1987. Then some 40 years after their initial interview, Linda found the transcript and donated it to the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, home to Hujar’s extensive photographic archive. Following a 2018 exhibition, the independent publisher Magic Hour released the transcript verbatim as a slim 56-page book, which has now been adapted into the film, Peter Hujar’s Day, starring and produced by the brilliant Ben Whishaw.

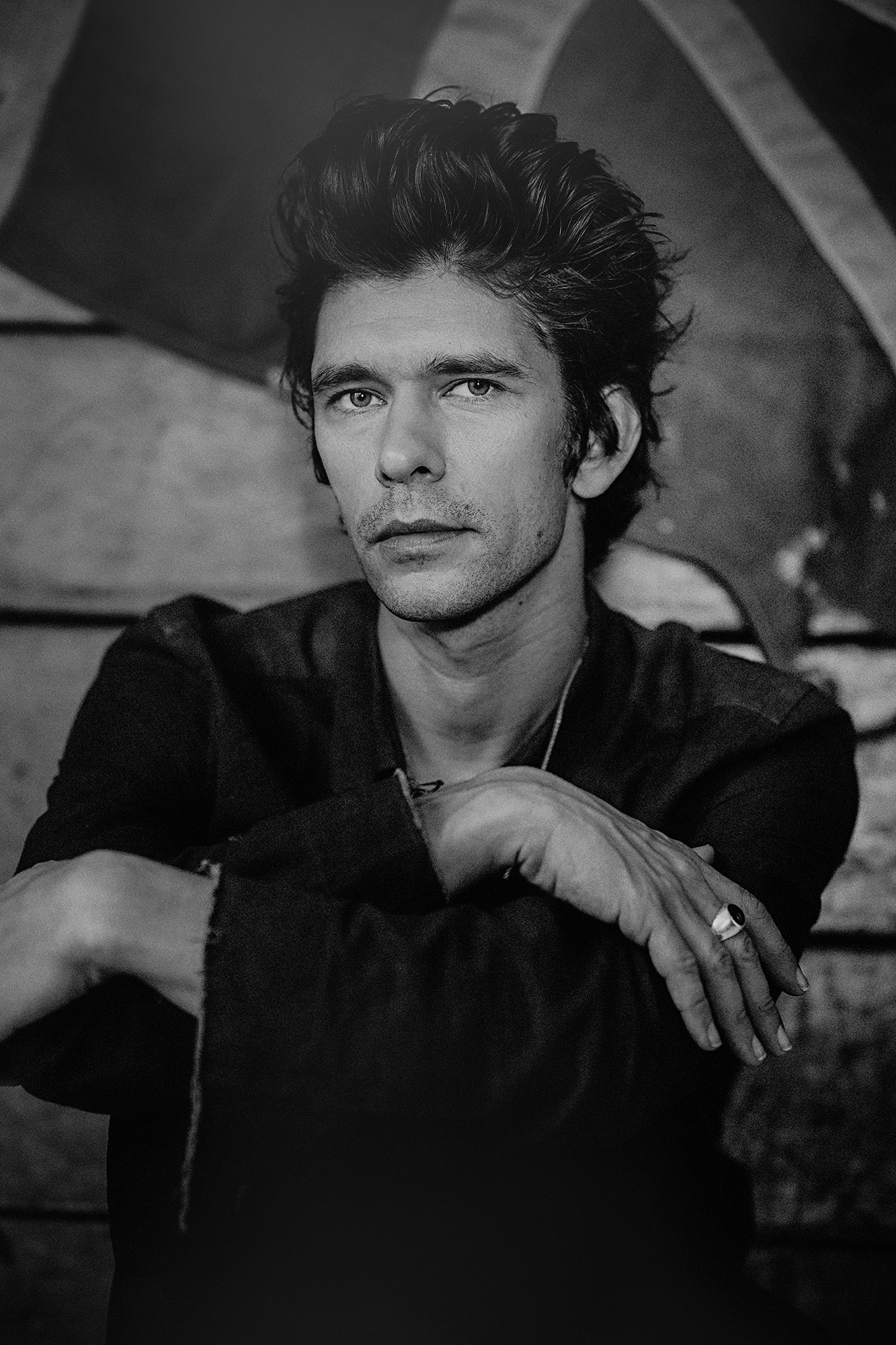

We meet on a rainy day in London during a press junket in a faceless hotel in Leicester Square. I enter the room and Ben is there, sat crosslegged on the sofa. He stands, we shake hands and make introductions. He is handsome, slim, wearing jeans and a brushed flannel plaid shirt by J.W. Anderson, with his hair tied in random scruffy top knots like some fabulous wonky boy version of a 90s era space bun Bjork. Ben is gentle, unshaven, smiley, and charming, exactly what you want him to be.

PETER HUJAR’S DAY, FILM STILL

Peter Hujar’s Day is an intimate two-hander set in a sun-faded New York loft in the 1970s, where Peter, played by Ben, is interviewed by Linda Rosenkrantz, portrayed with effortless elegance by Rebecca Hall. Peter regales Linda with acute details about the day before including his sleep patterns (he’s often very tired), phone calls, irritations and work worries whilst smoking endless cigarettes and chugging down drinks. They wander from room to roof and back again. From day through to night they stare at the Hudson River and the ever impressive New York skyline and languidly loll around each other, touching, resting, dancing as they share an intimacy and ease normally reserved for lovers.

It is an unconventional biopic. It doesn’t tell Hujar’s life story. Instead it allows us to share a moment with him in what feels like real time, so much so you feel like you are there, breathing the same air. It’s an experience akin to watching a stage play. There are no blockbuster explosions or VFX here, the solitary moment of thrill being an impromptu dance to Tennessee Jim. Ben inhabits Hujar with delicacy. He is captivating and his words spark your imagination as he recounts photographing a curmudgeonly Allen Ginsberg or a phone call with Susan Sontag, iconic names which litter his conversation with such honesty you feel almost guilty, as though you’re eavesdropping.

In 2021 Ben had wrapped filming the provocative throuple drama Passages with Ira Sachs. On completion the seed of a new project was quietly planted. “Just after we’d finished Passages, Ira gave me the book Peter Hujar’s Day and asked ‘Do you think there might be a film in this?’ I really liked it, but I didn’t quite see what it could be.” A year later and completely out of the blue, Ira sent him the finished script. “It sang to me in a way I hadn’t been able to imagine on the page. To be honest, if Ira asked me to come and read the phone book for him, I’d probably say yes. I just really, really wanted to be in his orbit and working with him again.”

The script sang to me in a way I hadn’t been able to imagine on the page. To be honest, if Ira Sachs asked me to come and read the phone book for him, I’d probably say yes. I just really, really wanted to be in his orbit and working with him again.

Ben Whishaw

The location, the set design and costumes nod to the era, with ornaments and artefacts perfectly placed to the point of reduction. At one point when Peter stands, I find myself admiring his perfectly worn-in blue jeans. That is something very difficult to get right. “We spent ages getting the clothes perfect, time I thought would’ve been better spent rehearsing, but Ira was correct,” Ben says. “Ira actually really doesn’t rehearse at all. You just begin shooting. It makes it alive in a way that I love. It took me about three months to learn the lines. I just walked around, endlessly going over it. But as I learned it, I was like, there’s no way this can be a short film because it’s taking me an hour and a half to say all of this stuff.”

Peter Hujar photographed New York in all its rundown, seductive scabbiness of the ’70s and ’80s, a period often romanticised through the lens of hindsight, when glamour bloomed in filth, though in truth the city was frightening, gritty and rough. He learned his craft on the job, developing the museum level printing skills that would later bring a striking classicism and authority to his portraiture. In lesser hands, his subject matter might have seemed squalid or perverse; yet in Hujar’s black and white elegance, portraits of men ejaculating, urinating, masturbating or sucking toes appear heroic and painterly rather than obscene. His lens documents without judgement, elevating the realities of a life lived on and in the margins. You can almost smell his subject matter.

PETER HUJAR’S DAY, FILM STILL

He lived and worked until the day he died in the apartment once occupied by Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis. Subjects included the streets of New York and desolate landscapes to the mummified corpses of the Palermo catacombs. He modelled for Andy Warhol, dated and collaborated with artists Paul Thek and David Wojnarowicz as well as activist Jim Fouratt, photographed members from the first-ever Gay Liberation Front, and counted Susan Sontag, Vince Aletti, Nan Goldin and Fran Lebowitz among his friends. A senior, stately presence to contemporaries such as Stanley Stellar, Alvin Baltrop and Leonard Fink, Hujar shared with them an unapologetic fascination with the long-vanished Chelsea piers, which became cruising grounds and queer spaces before queer spaces officially existed. They have since become mythic: the piers were torn down, and only the photographs remain. He also captured dogs, sheep, horses and cows with the same beauty and respect he brought to his portraits of Rudolf Nureyev, Greer Lankton, Divine, John Waters, William Burroughs, Lou Reed, Cookie Mueller, The Cockettes and Quentin Crisp.

Ben first encountered Hujar’s work on the cover of Antony and the Johnsons’ now-iconic album I Am a Bird Now. The startling image Candy Darling on Her Deathbed shows another Warhol superstar reclining in her hospital bed, surrounded by flowers, looking at once sensational and heartbreaking. Candy would die of lymphoma within a year of the portrait being taken. He later realised that Hujar’s work had been hiding in plain sight throughout his life. A Little Life’s now-famous cover, the 1969 photograph Orgasmic Man, with its ambiguous mix of ecstasy and agony, was Hujar’s too. And so were the postcards he once collected of men with thick, hairy chests wearing dresses which he’d held onto without yet knowing their author.“Around the pandemic, because I finally had the time, I really, really got into him,” Ben says. “And then I was like, ‘Oh, wow—this guy is just sublime.’”

Around the pandemic, because I finally had the time, I really, really got into Peter Hujar. And then I was like, ‘Oh, wow—this guy is just sublime.’

Ben Whishaw

Is he lucky enough to own any of Hujar’s photographs? “I bought one around four years ago. It’s a self portrait. He’s naked in a chair, sitting in his loft, looking directly at the camera. And it’s so beautiful. It’s called something like Seated Self Portrait 1980 (Depressed). I think he was going through a particularly difficult time. But he’s sort of sexy in it. His tummy is sticking out and he’s looking almost challengingly at the camera.” Why did you choose this image? “I felt stopped in my tracks by it. I feel like he’s challenging me to be honest. There’s something provocative and demanding about his gaze. It’s like he’s insisting on the truth. That’s what I think when I look at it.” And where does Peter live in Ben’s day to day life? “He’s in my hallway, next to the door. So every day, in and out, there’s Peter. I feel very connected.”

How does the internal pressure manifest when playing someone he reveres? “My way in is to see it only partly as truth and partly as fiction. It’s what me and Ira and Rebecca are creating so it has a basis in Peter but it’s not completely Peter. It’s fiction that we’re making, so that gives us a license.”

The chemistry between Ben and Rebecca Hall is one that feels authentic, like best friends or even partners, it reads as effortless and still. “Ira would give us notes, saying ‘just very, very, very relaxed. No effort at all. Do almost nothing.’ So you end up getting into a vibe that’s very comfortable,” Ben says. “I realise how rare that is. You hardly ever get to see those kind of states depicted in films which are usually about very charged and dramatic things. I like that about this film that it’s kind of… soft.”

Any worries that the movie might be boring were, in fact, actively encouraged. “I have this interest in very slow films. I feel strangely refreshed by them. So rightly or wrongly, I was always like, it is what it is. If some people find it boring, that’s fine. I felt kind of quite strong in that. And I found it personally so interesting that I didn’t really care. I found the script so fascinating as a text that it didn’t worry me.”

Earlier this year, the Hujar retrospective Eyes Open in the Dark opened at Raven Row in Spitalfields, an ornate gallery fashioned from two conjoined houses built in 1690. The space felt like a ghostly mausoleum: a former home stripped of domesticity to an all-white gallery with sweeping stairwells and empty fireplaces. It created a haunting environment that complemented Hujar’s stark photographs, shown alongside Warhol’s Screen Tests and portraits by David Wojnarowicz. The result was astonishing.

As his contemporary Robert Mapplethorpe amassed notoriety, fame, money and acclaim, Hujar remained an outsider, held back by his own perfectionism and his inability to reconcile artistic integrity with commercial success. He resisted compromise, maintained standards few could meet, and dismissed anything he deemed impure or unintelligent. He refused to bend to expectation.

It has been twenty years since I Am a Bird Now, ten since A Little Life, so why does Ben think Hujar is only now gaining the traction and recognition that eluded him in his own lifetime? “That’s a really good question. I’m not really sure why… I think he really was a truth-teller. They’re not idealised, cleaned-up pictures of people. There’s something raw about them, something intimate and something true. And maybe that speaks to people now. When I look at them, that’s what I feel.” He elaborates, “so much of our world is people putting forward an idealised version of themselves, and he doesn’t do that. He just shows people plain and true and, as I say, imperfect. I find that very consoling.”

PETER HUJAR’S DAY, FILM STILL

I think Peter Hujar was a truth-teller. They’re not idealised, cleaned-up pictures of people. There’s something raw about them, something intimate and true… So much of our world is people putting forward an idealised version of themselves, and he doesn’t do that. He shows people plain and true and, imperfect. I find that very consoling.

Ben Whishaw

Unlike Hujar, Ben flits effortlessly and elegantly between the mainstream and avant garde. How does he marry these worlds with such ease? “I like being tested and challenged. So I wouldn’t want to stay just in one territory. The older I get, the more I am interested in making things that are smaller and have a feeling of being handmade. Maybe that is where my heart really lies at the moment.”

Do you feel that Peter struggled with this dichotomy? “I think that Peter Hujar’s work is absolutely beautiful. I think that it may have been more to do with homophobia, and his own inability to sell himself. I think there may have been internal obstacles. I don’t think he liked commerce, you know, selling things. I don’t think it was an easy thing for him to do. His work was so personal and so intimate. I think he could be a complicated, difficult person at times.”

In his recent Criterion picks, Ben cites Derek Jarman as a hero. “When I was about 27, I discovered his house and garden in Dungeness. I started to read his diaries, and they were really transformative for me. I felt like he was saying something to me about how you could live your life as a gay man, something I had been perhaps avoiding or fearful of, and I felt like I went through a kind of liberation reading him. He taught me how you could be sexually free and creatively free and how the two are connected. He really didn’t try to win the favour of the mainstream, or heteronormativity. I mean, he really didn’t compromise at all. He just made very odd films with his friends, really. But they’re so creative, they speak so richly of that time, don’t they? And they’re still provocative. Sebastiane, in Latin, with those naked men frolicking around on a beach. Just wonderful.”

A fan of directors Gregg Araki, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tsai Ming Liang, Andrew Haigh and Todd Haynes, Ben is excited about the current state of queer cinema. “I’m desperate to see Pillion,’ he confirms. In a world where being queer is both celebrated and, in equal measure, attacked and feared, how important is it to have this constant narrative through your work? “The world is so different from when I started acting. It wasn’t said explicitly, but it was conveyed strongly to me as a young actor that you had to appear to be straight if you wanted to keep working. It’s so important to me to make queer art.” Simply by having Ben’s name attached to this project a new audience will find its way to Peter Hujar. His reach is a meaningful one, and here he uses it with intention.

The world is so different from when I started acting. It wasn’t said explicitly, but it was conveyed strongly to me as a young actor that you had to appear to be straight if you wanted to keep working. It’s so important to me to make queer art.

Ben Whishaw

Peter Hujar’s Day feels like the start of a thread being gently pulled. The Film Independent Spirit Awards, widely regarded as an indie precursor to the Oscars, recently nominated Peter Hujar’s Day in five categories: Best Feature, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Supporting Performance and Best Lead Actor for Ben. In recent years, Anora, Past Lives, and Everything Everywhere All at Once have followed a similar exciting trajectory. And in New York magazine’s 2025 Year in Culture round-up, Culturati 50 honouree Lindsay Lohan named Peter Hujar’s Day the most underrated work of the year, praising its “quiet beauty.”

You want to spend more time in the company of Ben as Peter, to push further into his life and open more doors into this hallowed world. The recently published Paul Thek and Peter Hujar: Stay Away From Nothing offers a tender portrait of their relationship told through photographs, handwritten postcards and letters. It is another small glimmer into a life we still know so little about.

When asked whether he has seen the book, and whether he would consider revisiting the role, Ben leans over and lifts a copy from beside the sofa. “Ira gave me a copy earlier. I can’t wait to read it. There’s lots of potential there. There’s so little that remains of him in terms of footage; there’s barely any video at all, which is hard for us to believe. And, tragically, of course, so many passed away in the AIDS epidemic.”

He pauses, reflective. “I feel aware that life is passing really fast. I want to do things that are really, truly meaningful to me. Things I can speak about.” He pauses, looks up then looks down before fixing his gaze. “To make films that come from a place of honesty. To tell a truth. Something I can give my heart to. Films I feel passionate about. That’s what I want to do.”